Marginal gains in the context of cycling refer to the practice of making small, incremental improvements in various aspects of a cyclist’s performance and equipment to gain a competitive advantage. This concept became particularly popular in professional cycling thanks to Team Sky (now Ineos Grenadiers) and their former performance director, Sir Dave Brailsford. The idea is that by focusing on many small improvements, collectively, they can lead to significant overall performance improvements. Since the Sky glory days, we’ve seen performance improvements across a number of endurance sports including cycling, triathlon and running – a large part of this is the accumulation of marginal gains.

A few weekends ago we had the Ironman World Championships in Kona, which was won by Lucy Charles-Barclay in no small part due to how aerodynamic she is (as well as obviously being a great swimmer and runner). Some athletes were less dialled than Lucy, however. We saw road helmets, slow chain choices and sleeveless triathlon suits and it dawned on us that Ironman is probably the sport where marginal gains accumulate the most.

How much difference did 1% make in Kona?

Aerodynamic testing is a process that takes place over a number of years and the gains accumulate over time. On average, athletes are more aero than they were ten years ago but the distribution of individual athlete’s aerodynamics is similar now with world class triathletes and time trialists somewhere on the spectrum of just muscling their way to results and being perfectly dialled.

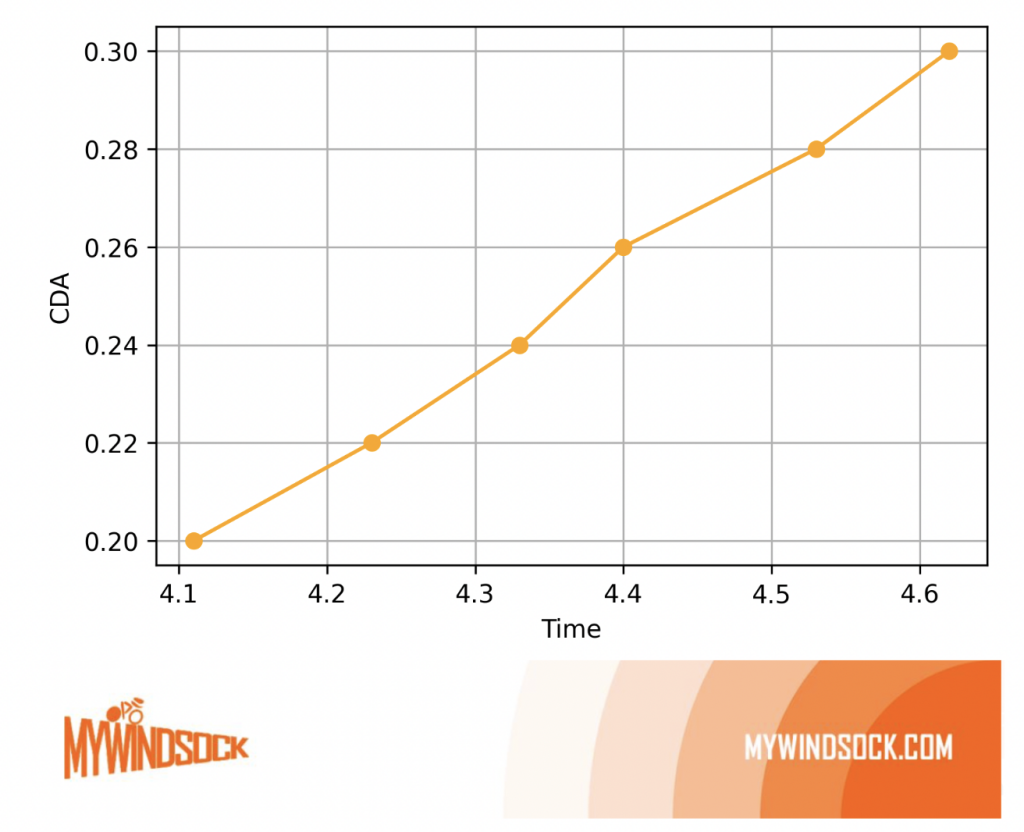

Over the years, the cda of the athletes competing at the pointy end of the race in Kona has dropped. We know this as athletes aren’t actually doing much more, if any, power than they were back in the days of two-piece triathlon suits and those weird triathlon crop tops. We just know now that those (awful) suits also weren’t very fast – among other gains found here and there. We can see how a ‘typical pro’ athlete’s time might drop as their cda goes from 0.3 down to 0.2 on the same day, pushing the same power…

Kona – a generational shift in times

Accumulating gains – a self fulfilling cycle

The other aspect worth considering here, as we see times tumble from one year to the next (myWindsock successfully predicted a Kona course record was coming) is that as riders go faster, they expend less energy. Energy is the integral of power with respect to time. What that means practically is the way you calculate how much energy has been expended is by figuring out how much power was done for how long and adding all of those bits up to get energy. Given that the amount of energy we have access to is the limiting factor in an Ironman, by reducing the amount of time spent on the bike we have more available energy left to run with. This means that athletes can run faster.

To answer our question posed, yes marginal gains still make a difference. Team Sky popularised the concept and Jumbo took it to the next level but the reality of it is that all of us still have unrealised gains and these can really add up. If you want to see how these look on your local time trial or triathlon bike leg, click here.

UK Time Trial Events

UK Time Trial Events