Today is the rest day of the Tour de France which has left us all sitting around and scratching our heads wondering what to do with ourselves. While I’m sure ITV and Eurosport are producing a glossy magazine show talking about some inspiring backstory surrounding Thibaut Pinot’s goats and Cycling Weekly are writing articles speculating around who feels good and who has shown ‘signs of weakness’ we decided to stay in our wheelhouse and talk about the impending time trial.

This year, the Tour has only one TT and it’s pretty short in terms of distance but that doesn’t make it unimportant. Big gaps in the general classification are possible as the course is a tricky one to pace correctly and we will see slow average speeds (relative to the usual insanity in Grand Tour time trials).

The course

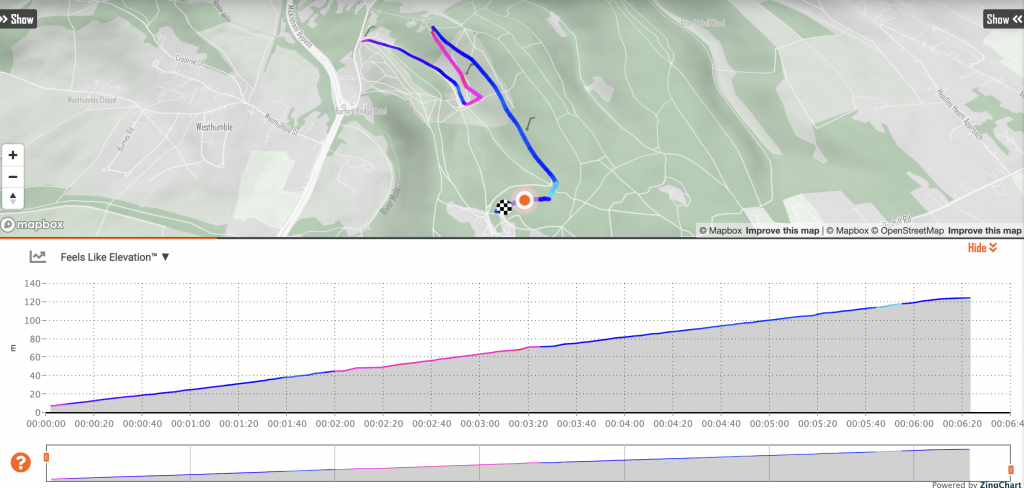

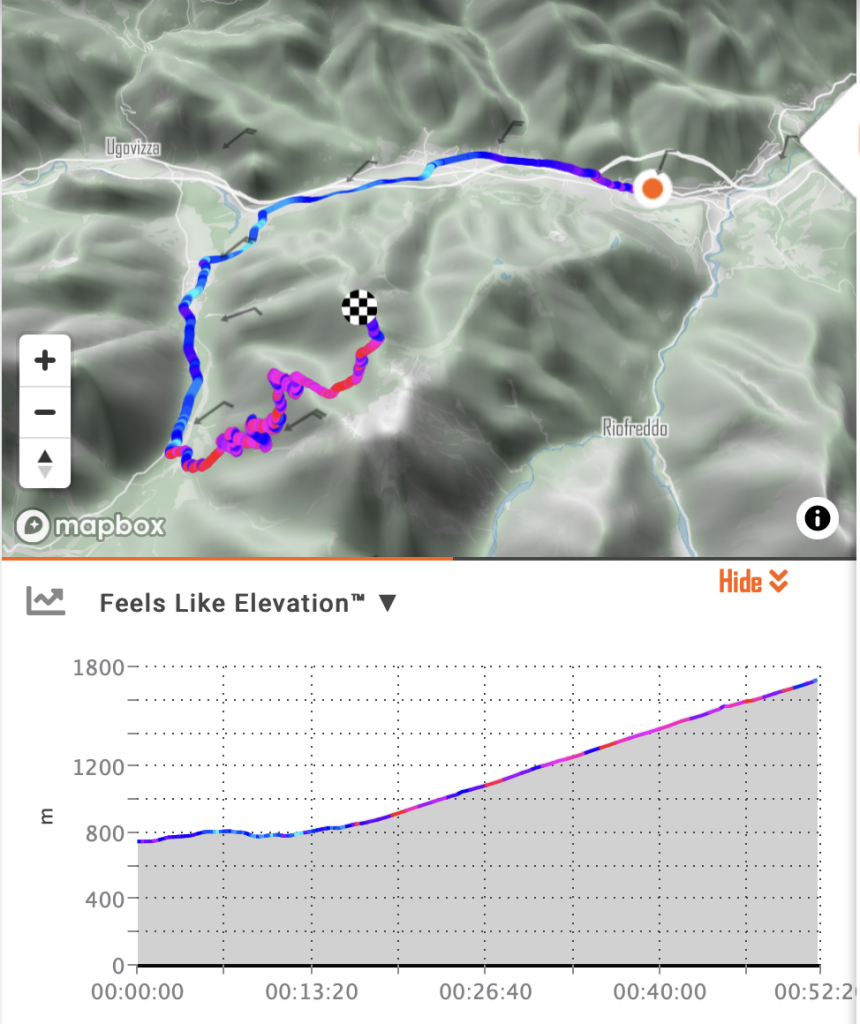

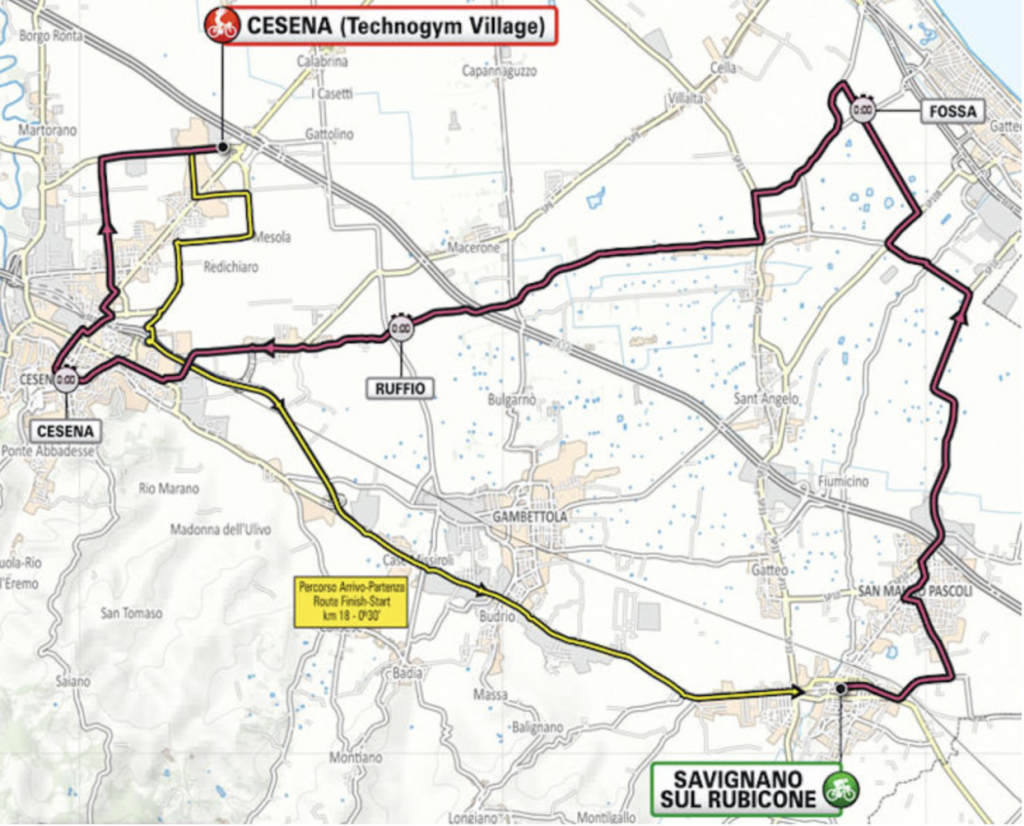

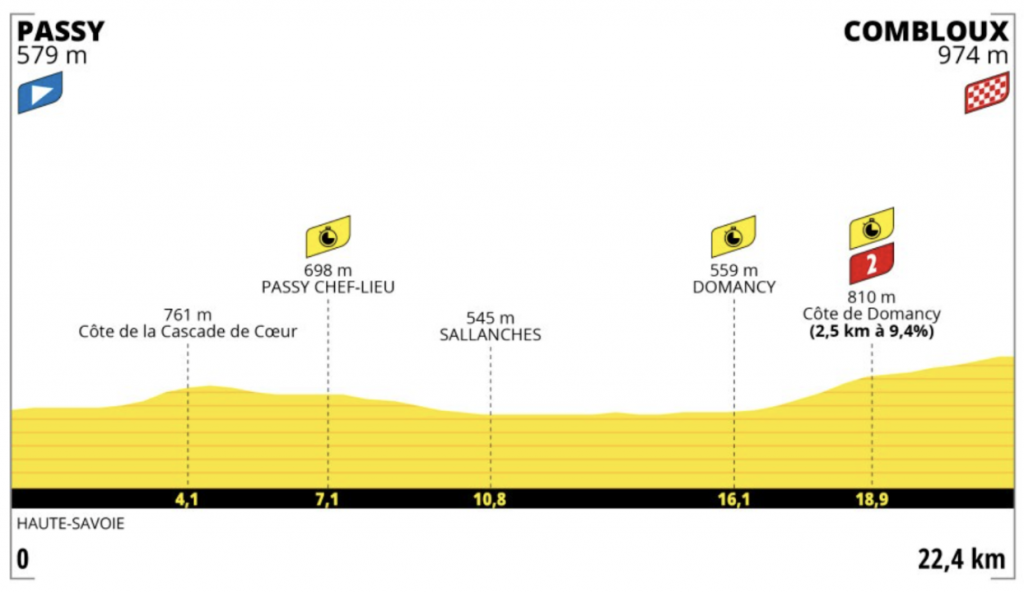

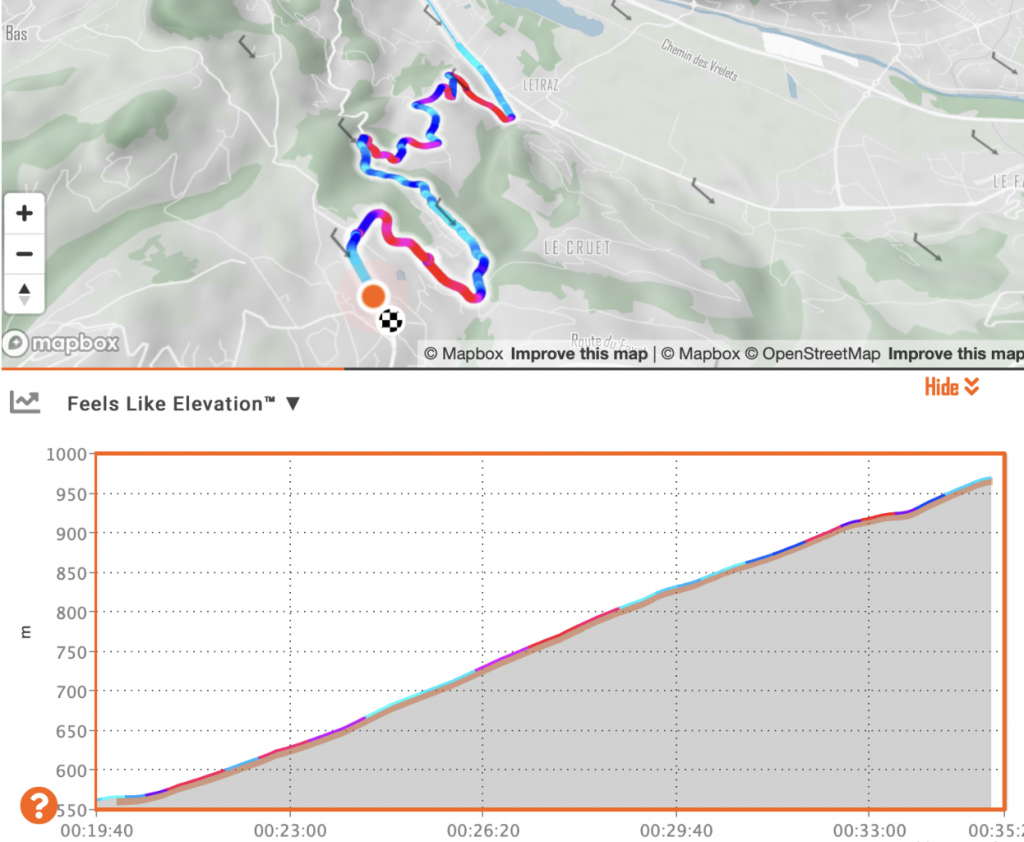

The TT takes place on Stage 16 of the 2023 Tour de France and the course goes from Passy to Combloux. It has 3 climbs, the Côte de la Cascade de Cœur, the Côte de Domancy and the ride up to Combloux to finish. The descent from Passy Chef-Lieu down to Sallanches is technical and the roads are narrow (though have been freshly resurfaced).

The slower speeds in this climb will be interesting as will the high temperatures often seen in this valley. The teams that have invested in the materials that provide a balance between aerodynamic performance, cooling and also aerodynamic performance at slower speeds (as the fastest fabric at 60kph is not often also the fastest at 30kph) will have a competitive advantage over the riders wearing their standard speed suit. The usual disadvantage will also apply to athletes in the leaders jerseys as these skinsuits are typically slower than the team’s kit sponsor’s model.

The Weather Forecast

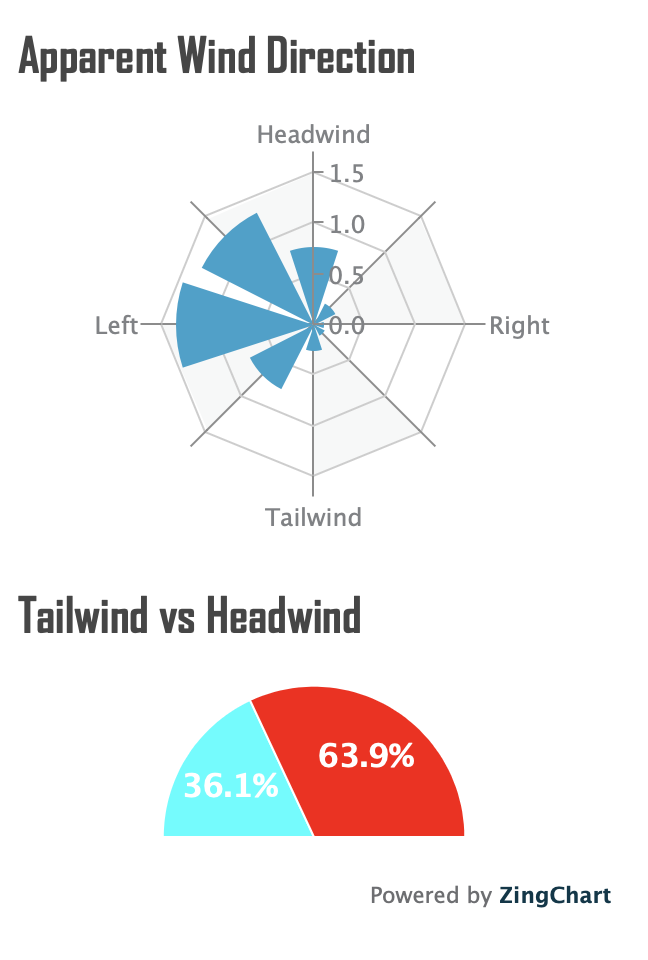

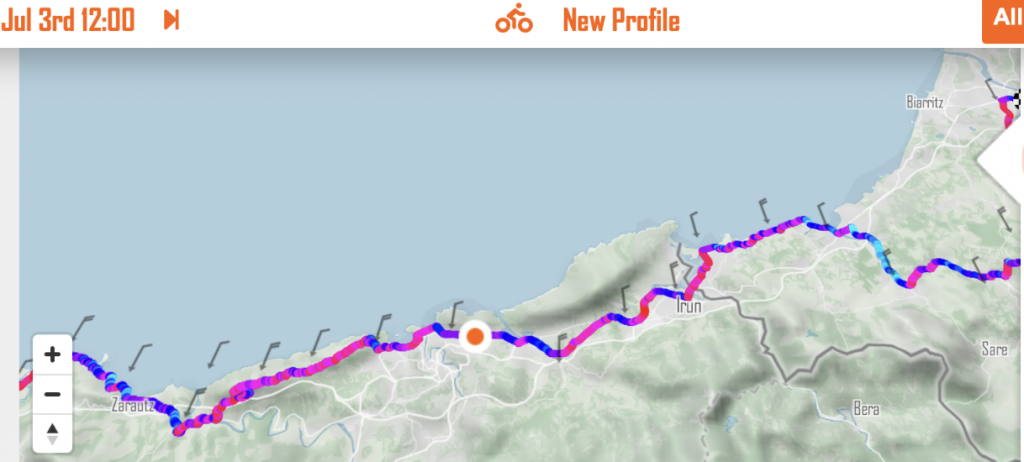

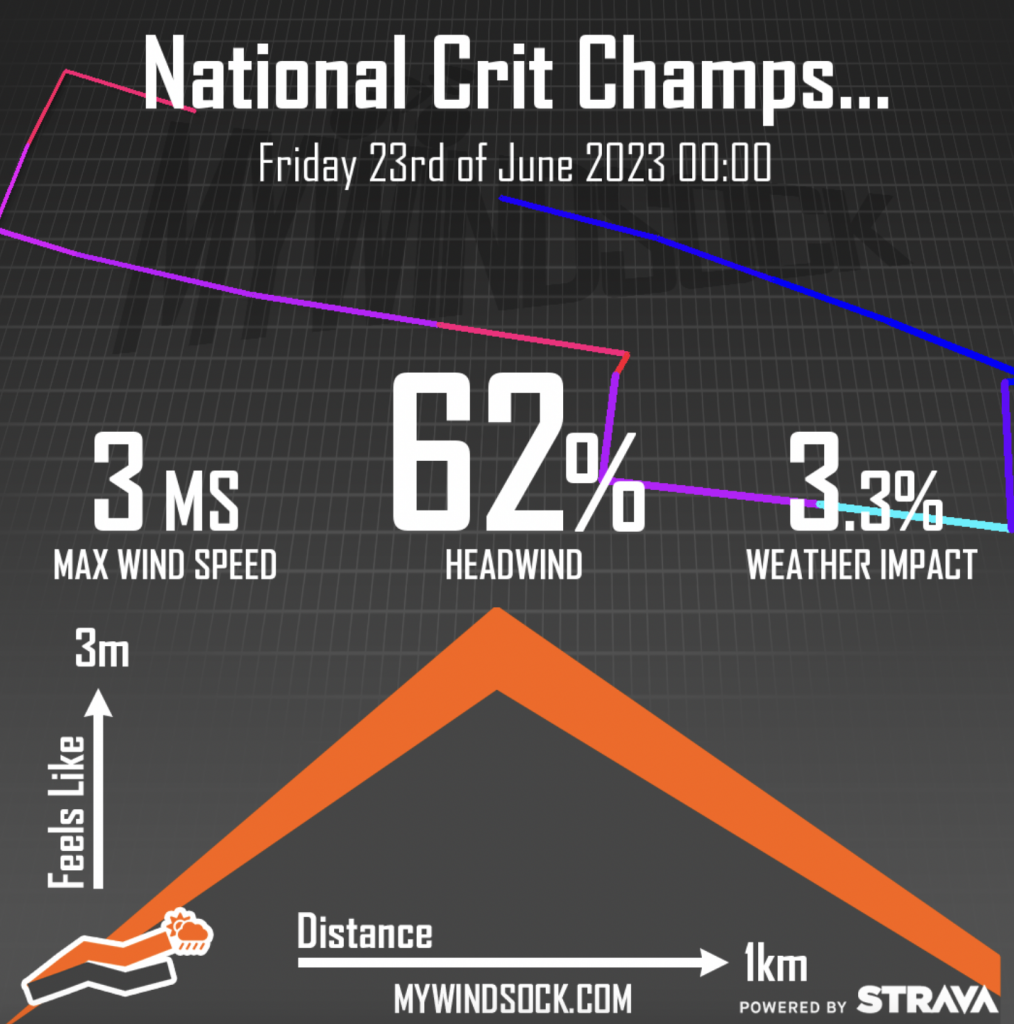

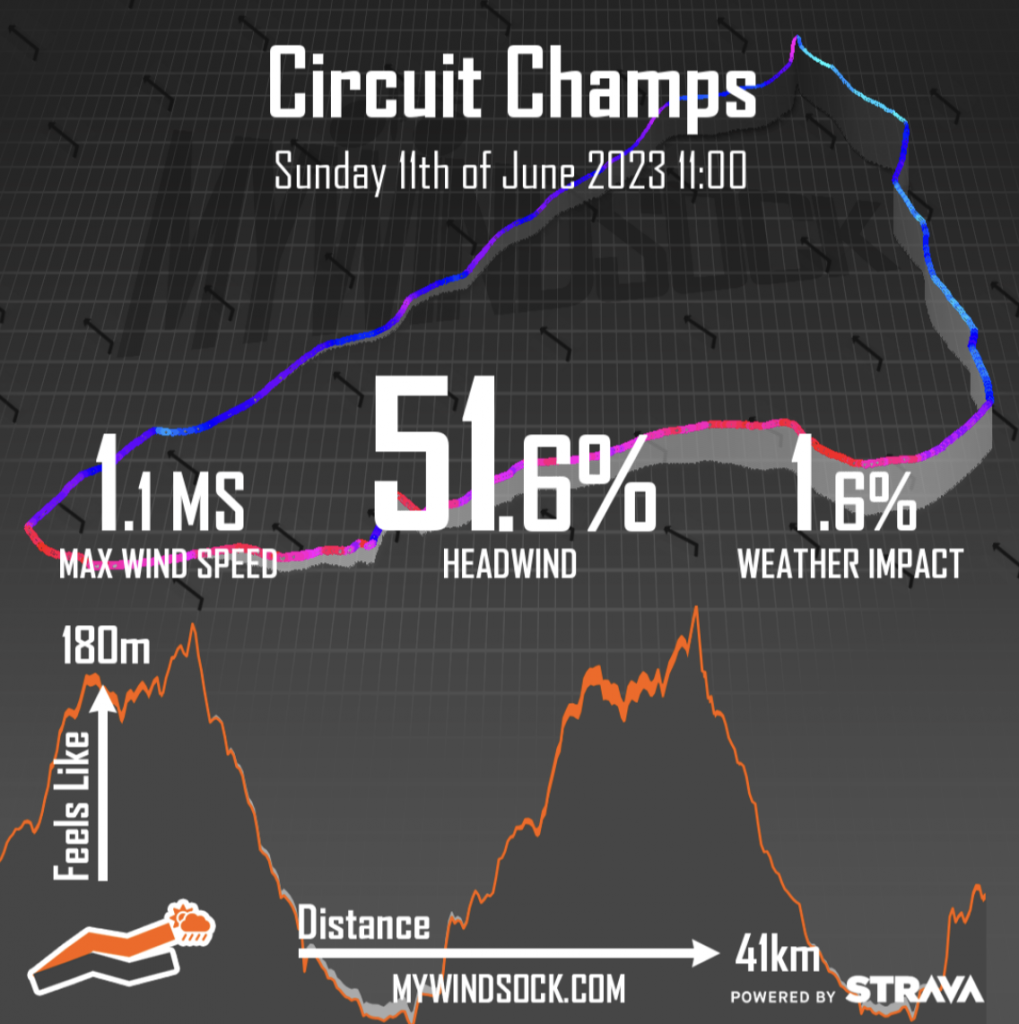

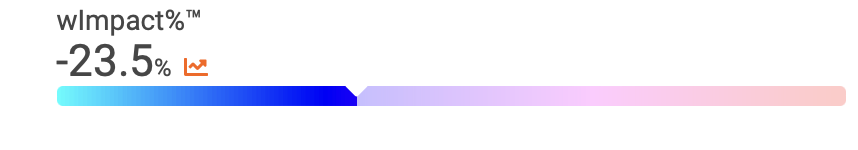

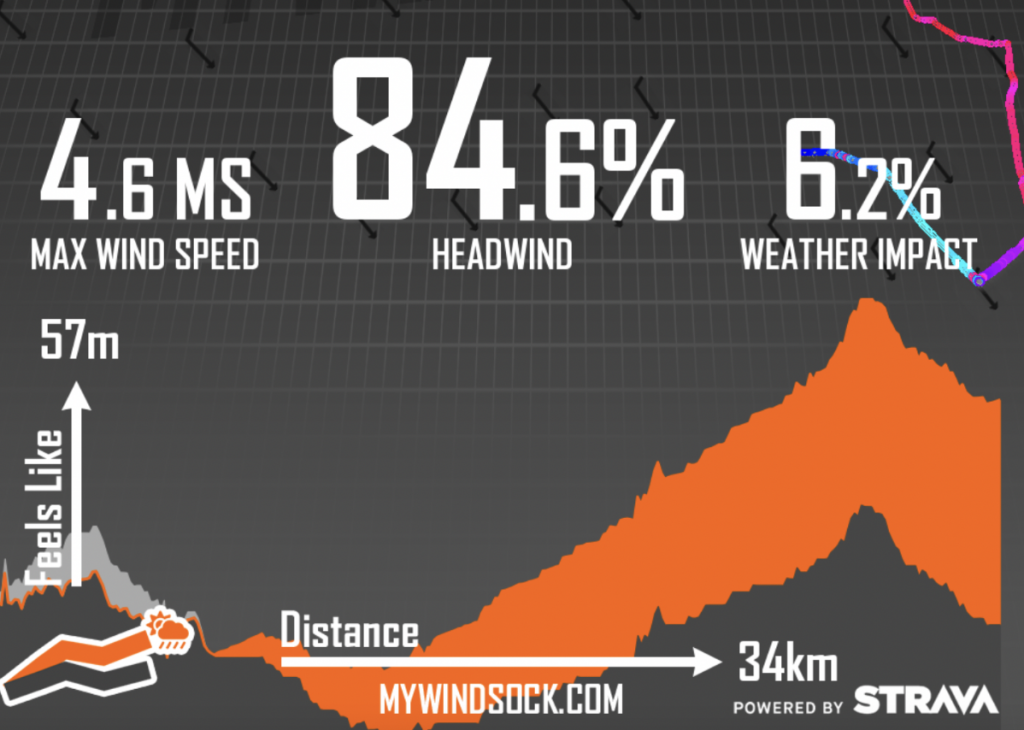

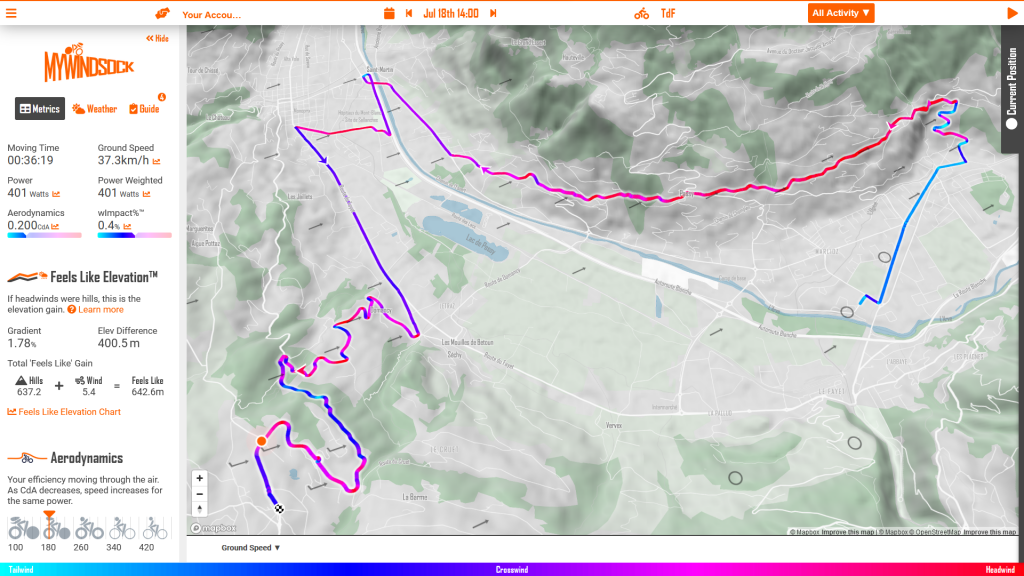

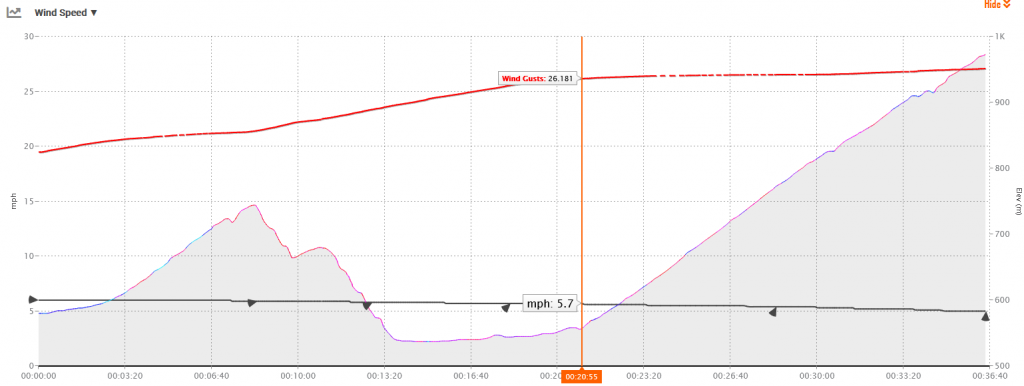

Due to Thunderstorms we are expecting very changeable conditions for the riders. Wind Speeds are expected to be predominantly South Westerly, at a Light Breeze of 6mph, with gusts of up to 27mph. The hot temperatures and intermittent showers will add to the complexity of the course.

On dry roads, a significant portion of the descent from Cote de la Cascade de Coeur towards Sallanches, could be taken in aero bars. However, the possibility of rain during the afternoon may cause riders to leave their fine tuned time trial positions more frequently. A wet vs dry descent is likely to be the greatest variable due to start time.

Expected finish times

The best place to stay apprised of the conditions on race day is via our forecast which you can find here.

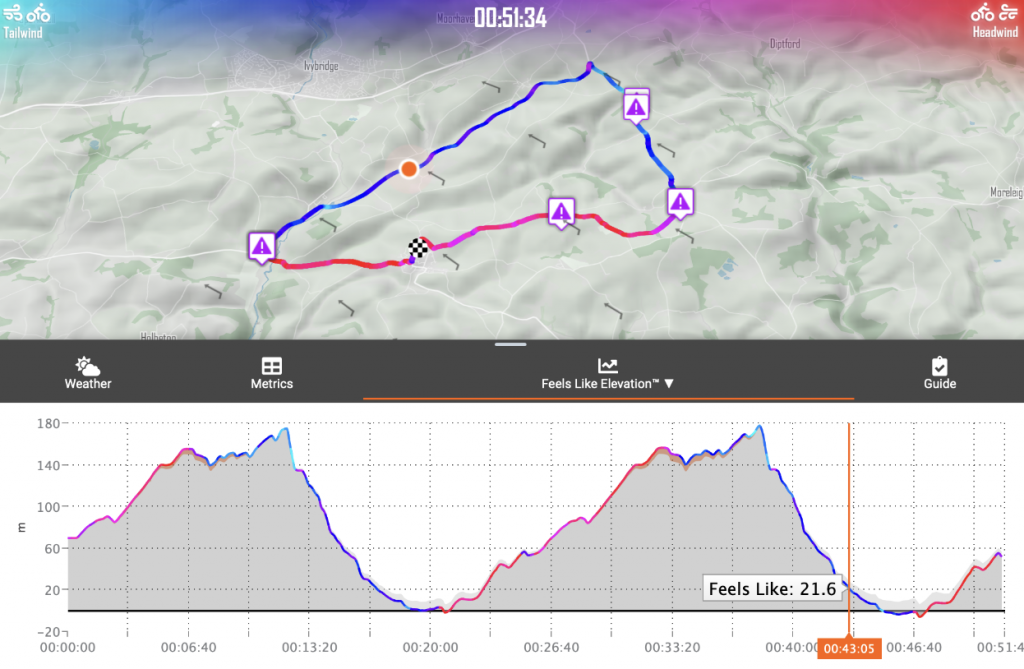

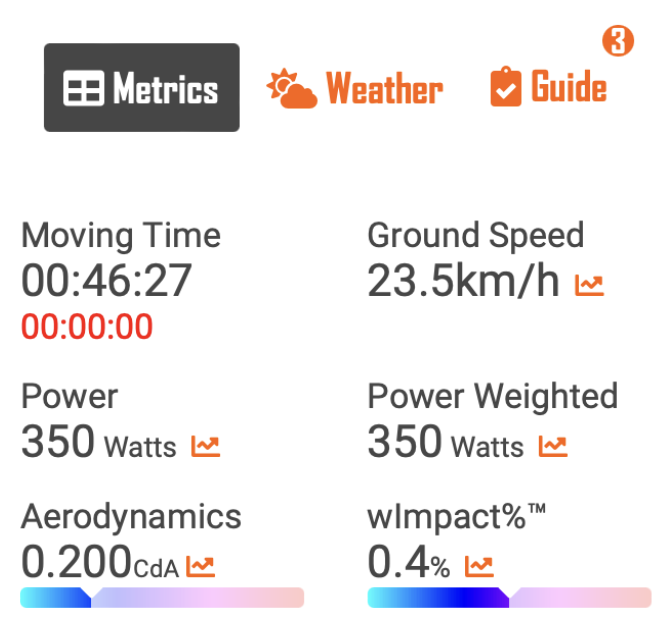

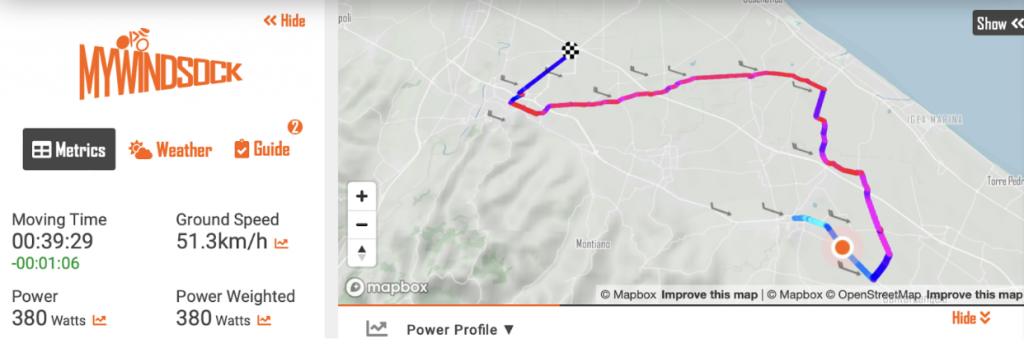

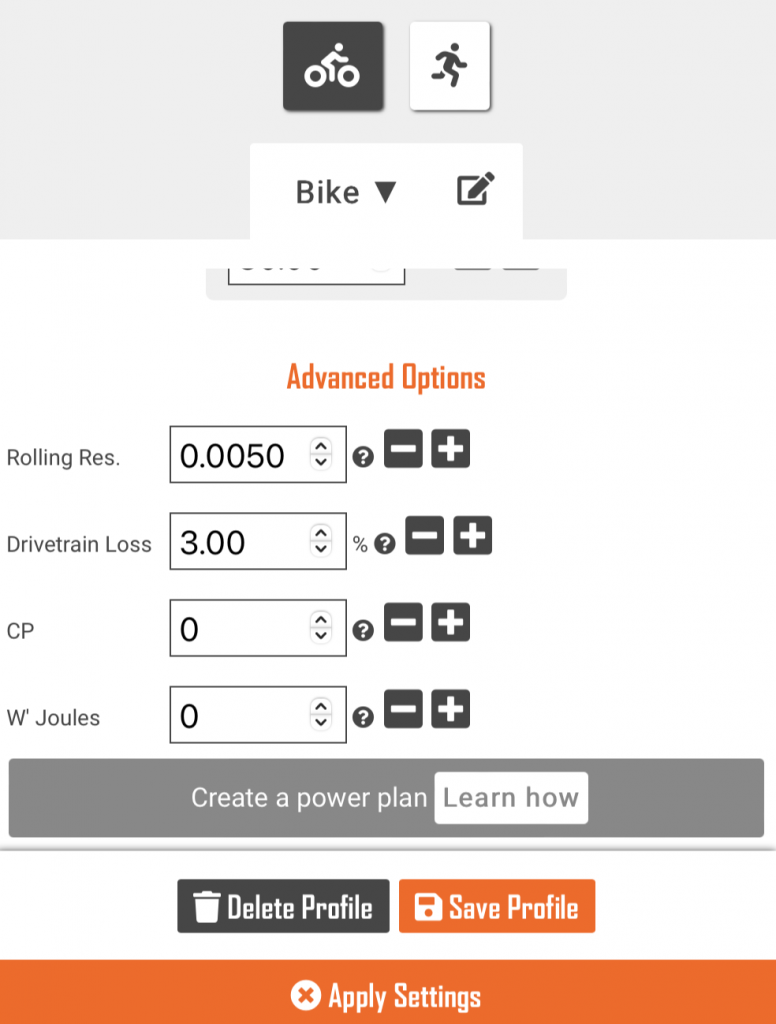

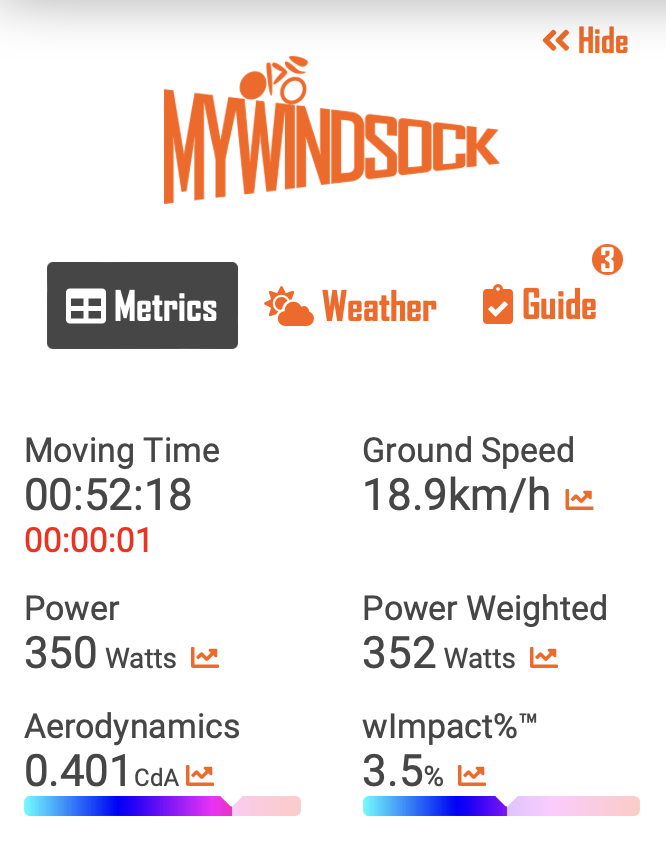

Over a course like this it can be difficult to predict finish times as the aerodynamic properties of riders change a lot on long shallow climbs. That said, the TT route is preloaded into myWindsock so we can check out the sort of times we might see based on a few power and weight options.

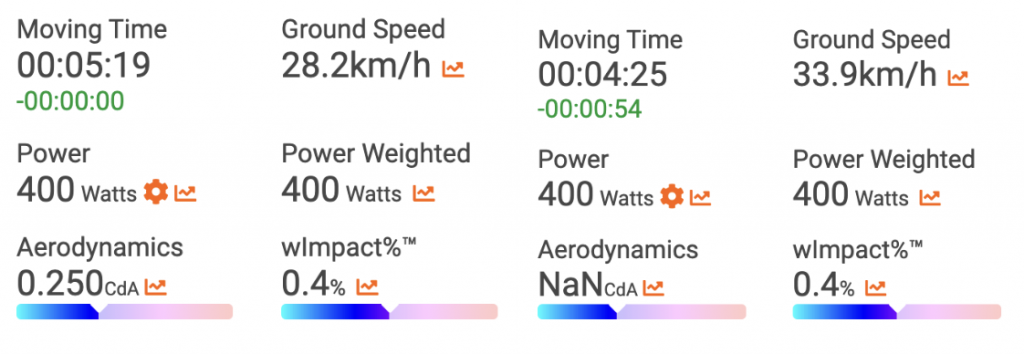

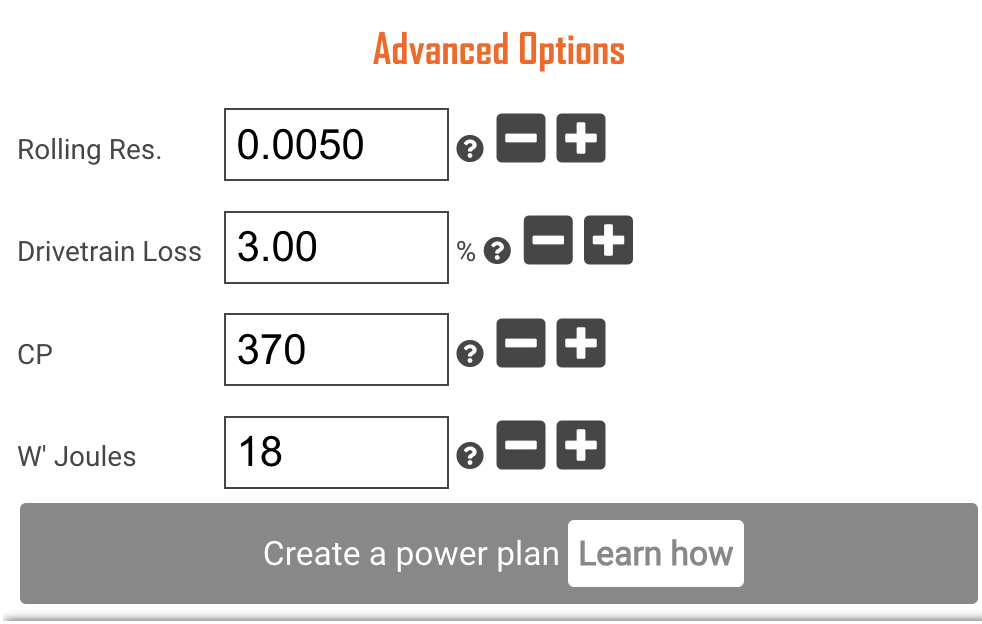

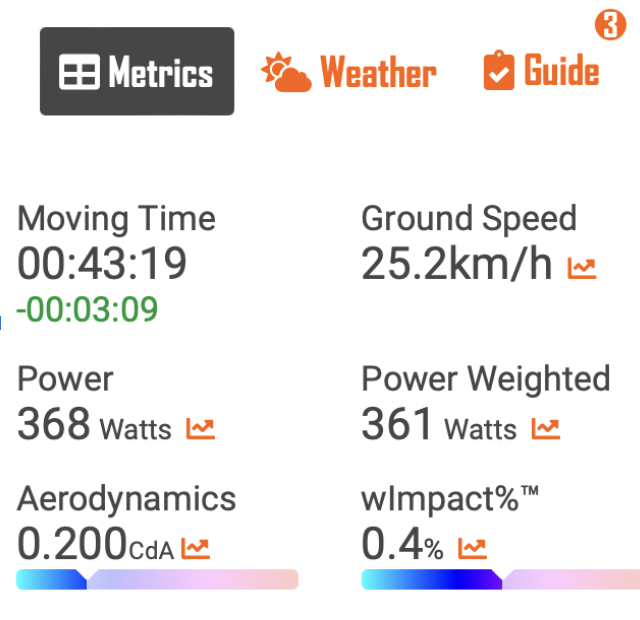

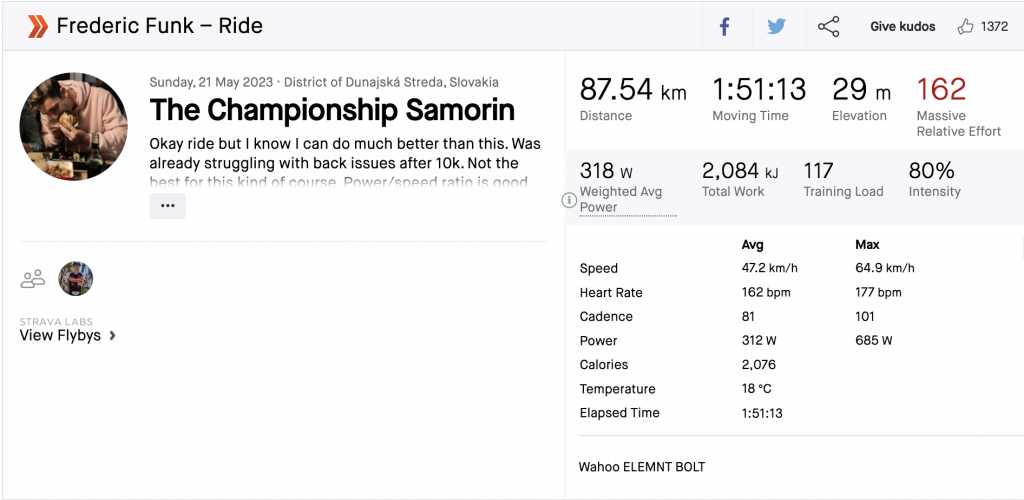

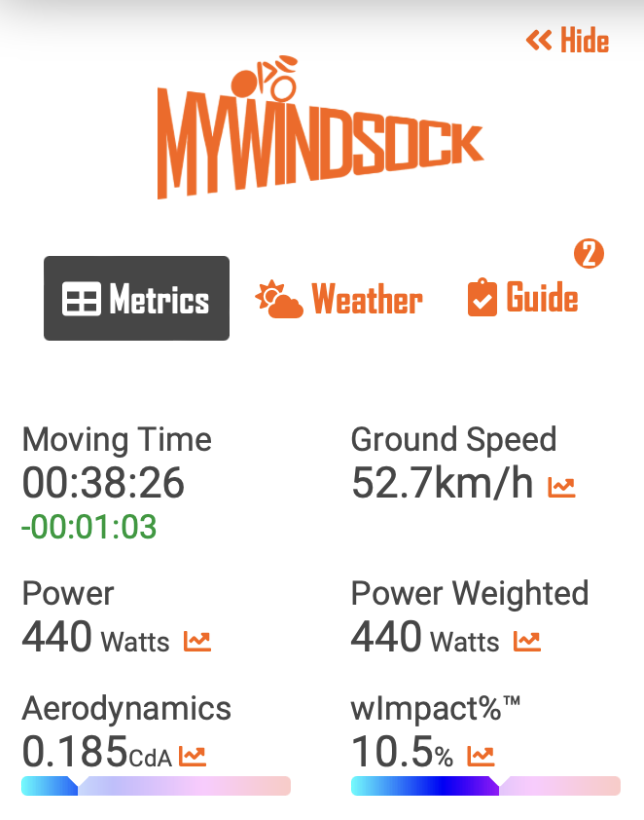

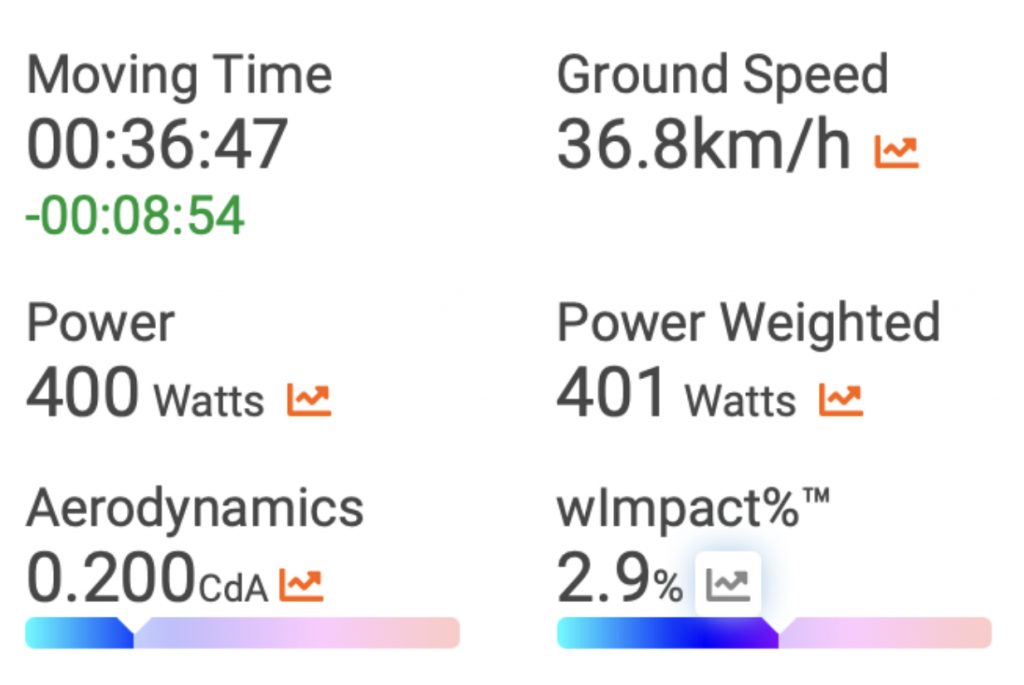

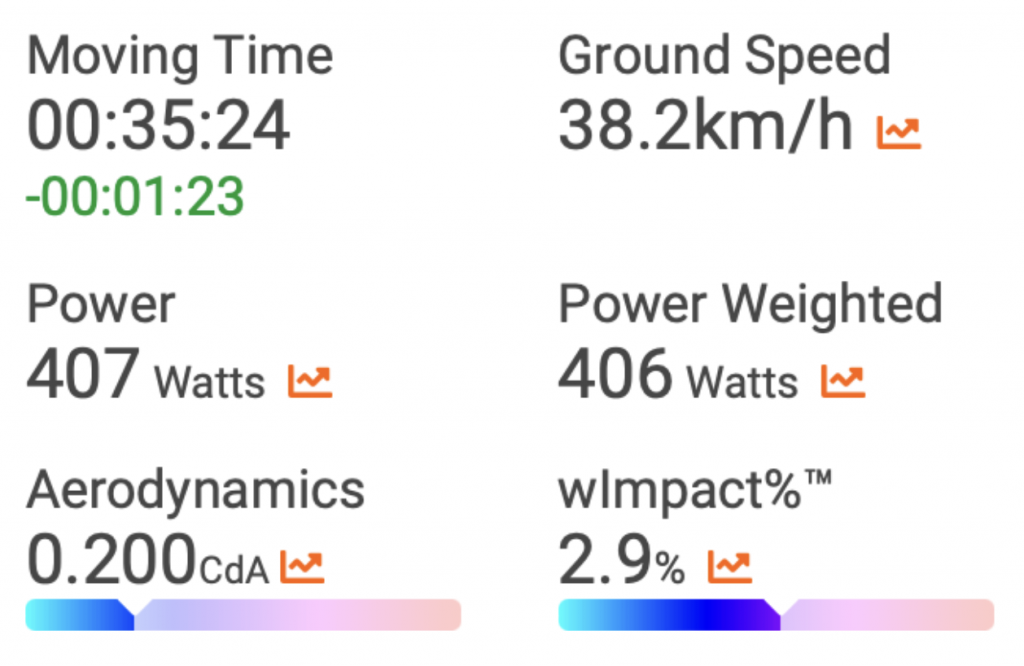

For this kind of race, we will think of a TT specialist with a cda of 0.2 and 400W to play with, along with a system weight of 75kg then we will play with the settings to see what a rider like Pogacar – the favourite in my eyes – will do in this TT.

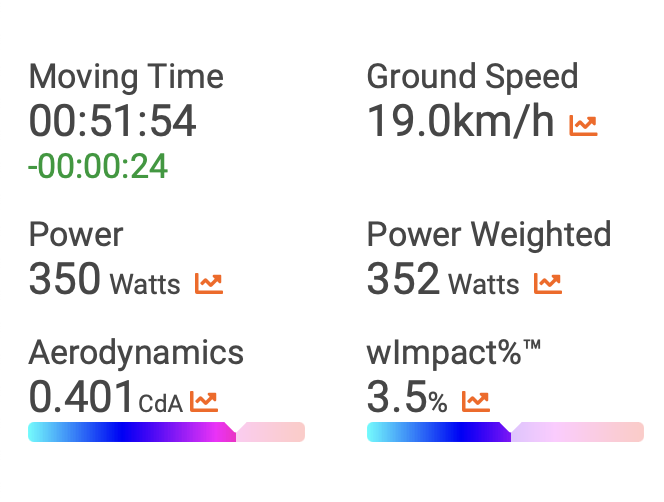

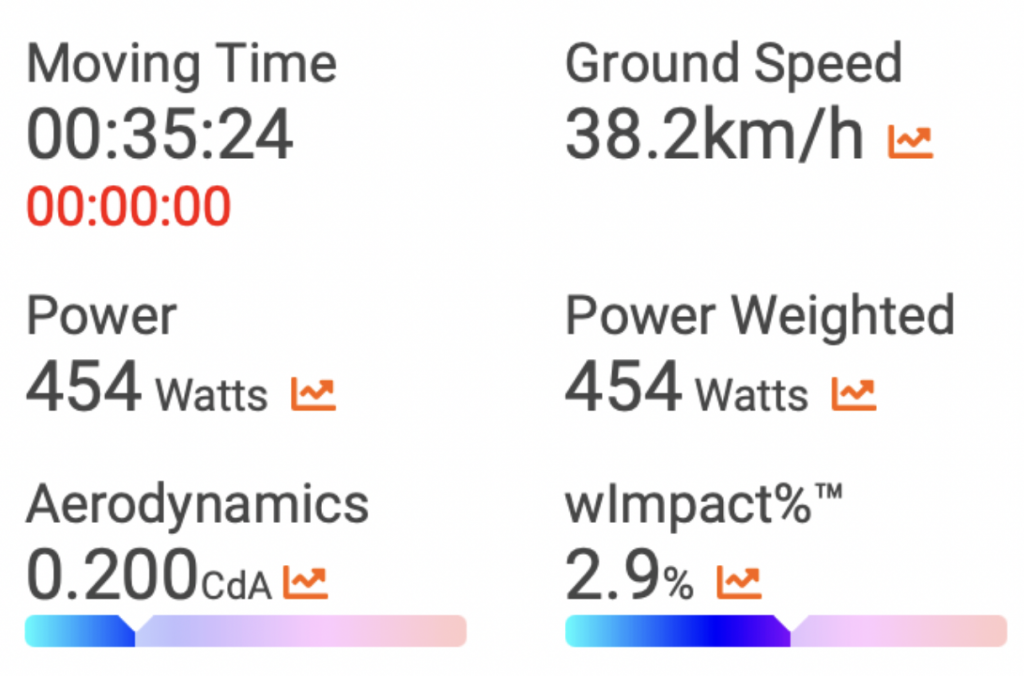

A solid benchmark for this first TT is under 37 minutes (weather pending of course). A GC contender will be able to do in the region of 6.1 W/kg for this duration and might have a slightly lower system weight of around 72kg. Let’s see what this does for the overall finishing time…

So the winner of the stage is likely to be pushing 35 minutes and it may come down to pacing strategy. This course also favours the lighter riders…

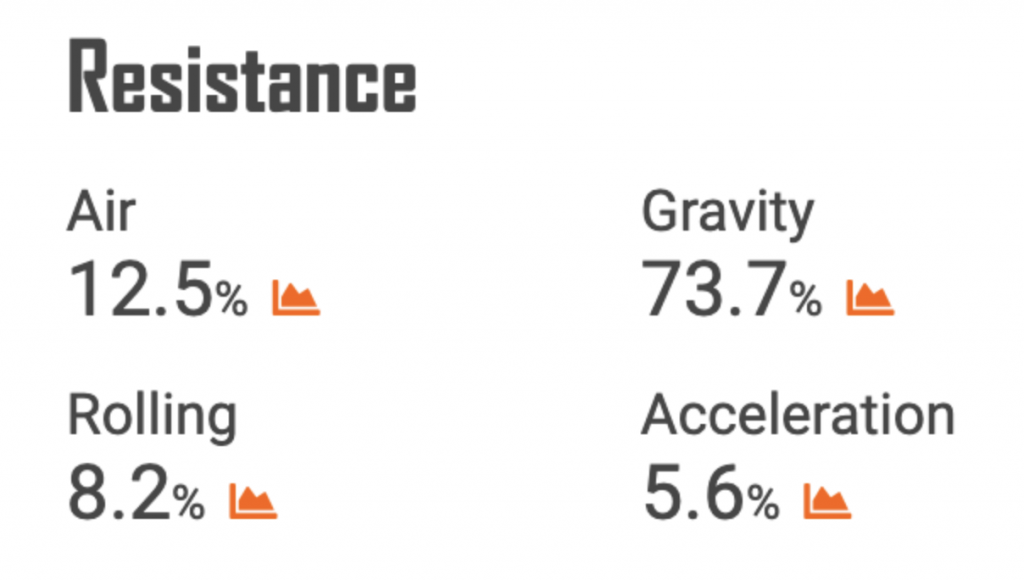

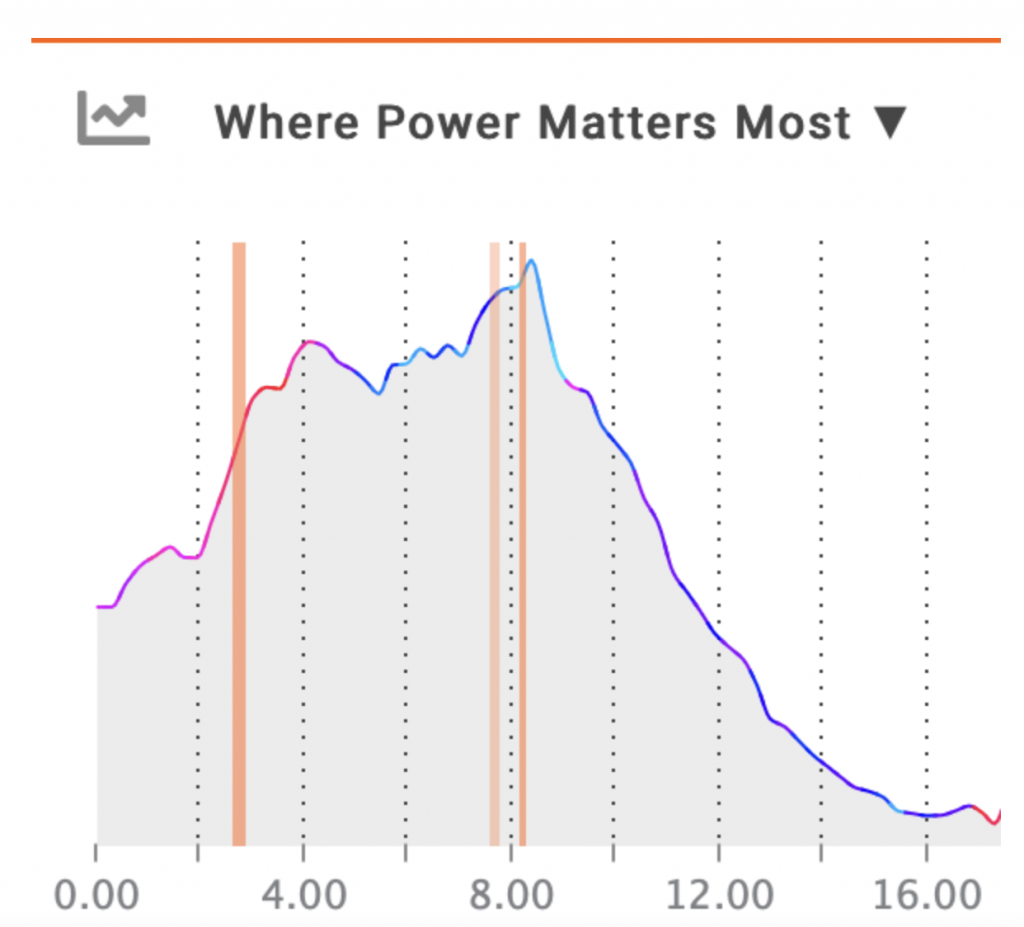

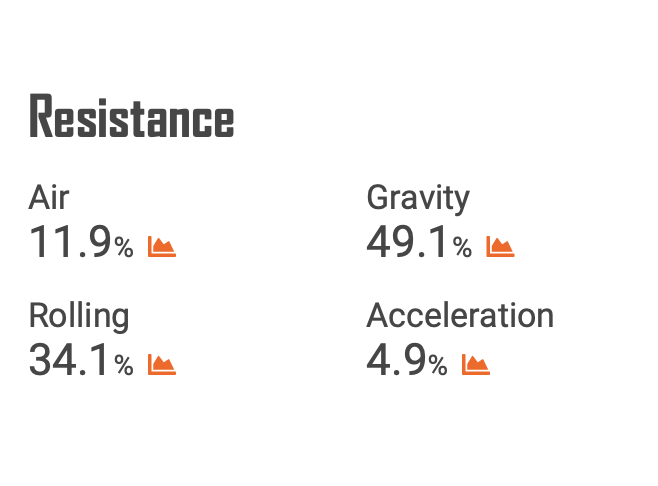

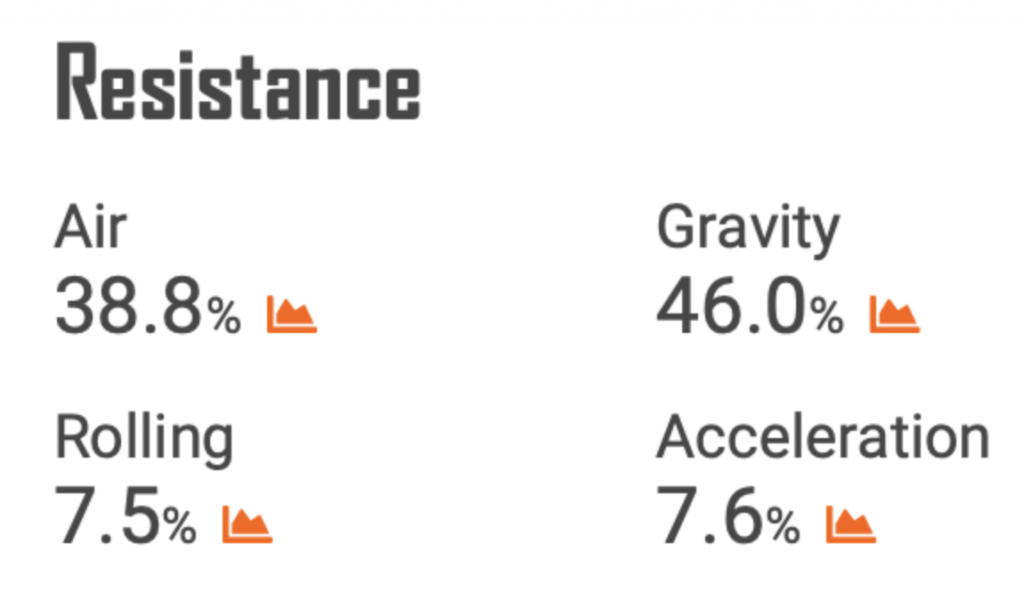

As you can see from our force breakdown, gravity plays a larger role than air resistance on this course – which is why I find myself frustrated when commentators describe it as ‘rolling’. This is a hilly TT that will suit climbers better. Yes the TT specialists will go better in the valley and yes the climbs are short, but the only bigger guy that stands any chance is Wout Van Aert.

Winning is possible for Wout – as we can see above, but he’ll need to do some monster numbers and it will need a bad day from one of the other main contenders.

Blowing up on the last climb

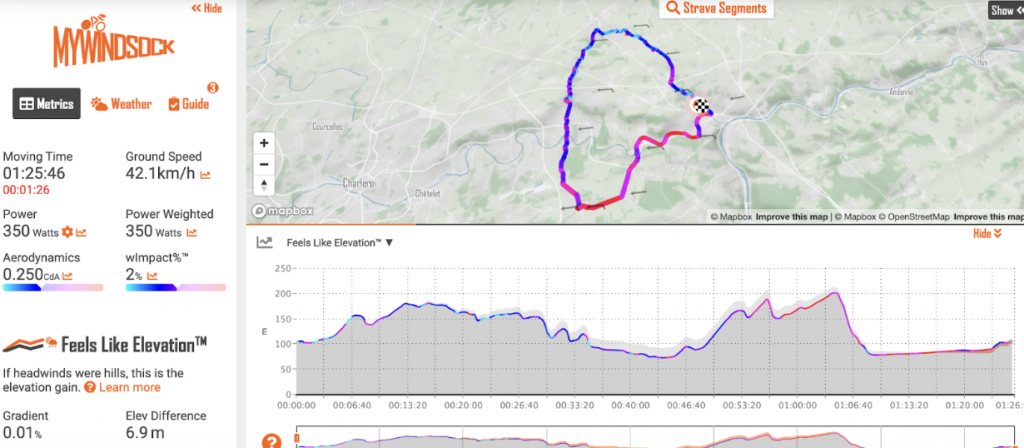

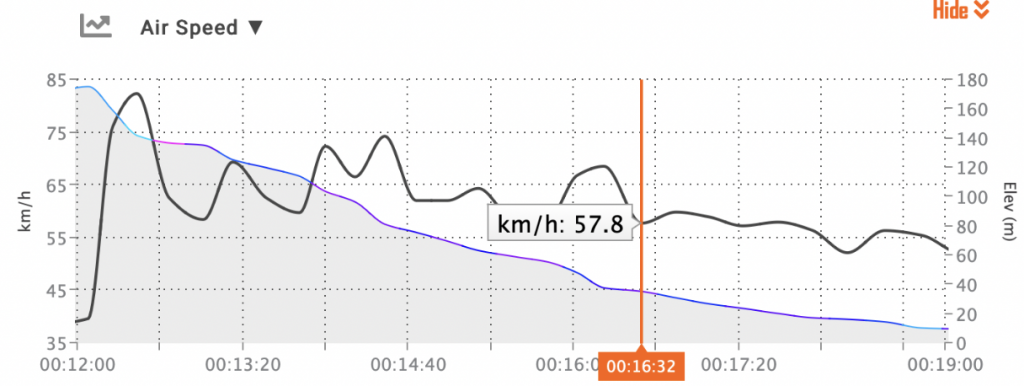

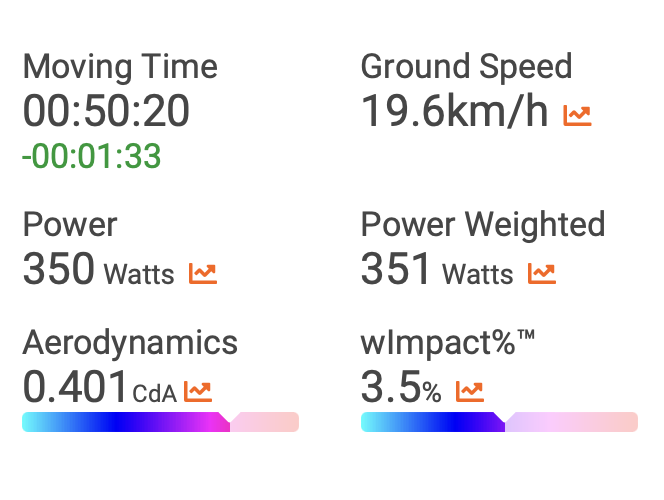

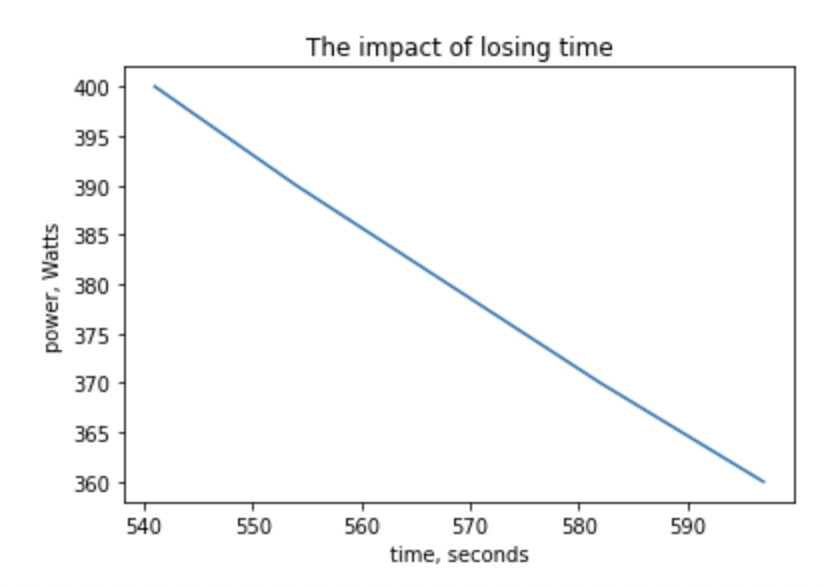

The last climb is steep and then turns out onto the main road where it flattens out to a low gradient for the final few kilometres. This low gradient section can be deadly though – it’s a big ring climb but it’s uphill all the way to the line. We thought we’d check out what happens if a rider cracks on this final segment by going too hard on the steep section – something we see often even in the pro peloton (think back to the final TT in 2021).

The final climb is steep and will take riders around 15 minutes from the base to the top. The first 2.5 km is steep and the final km flattens out and goes onto a main road.

What happens if a rider blows up then?

This TT is going to be important for GC but not long enough that it will decide the race. The overall winner is likely to be a GC contender but it could be won by a rouleur on a very good day. If you want to keep up to date on the conditions on the day, follow myWindsock on Instagram where we will be keeping up to date with the fastest conditions and providing live analysis of the time trial.

If you want to have a go yourself at predicting times and winners, or want to add a new level of precision and preparation to your riding – why not use myWindsock and sign up here.

UK Time Trial Events

UK Time Trial Events