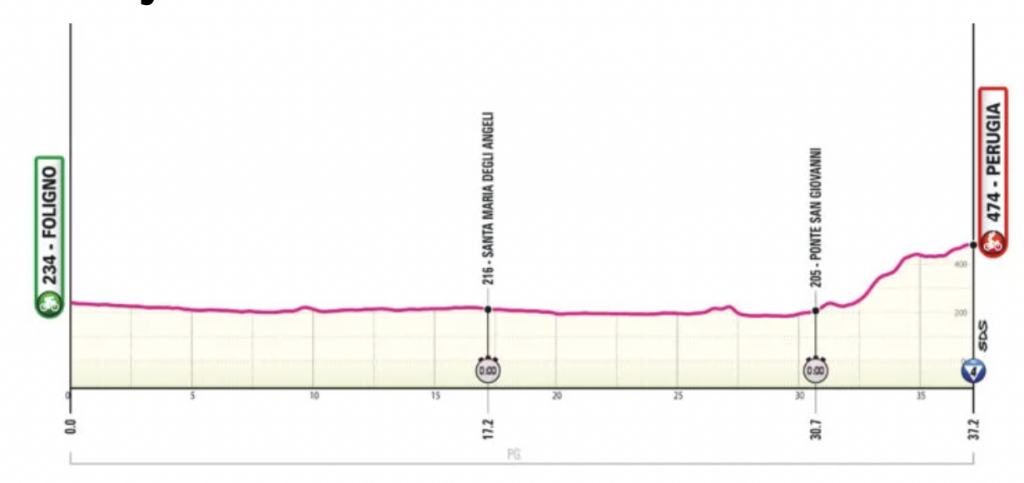

The Italian Grand Tour boasts 68.2 kilometers of individual time trials and culminates in a final-week mountain showdown. However, compared to recent years, there is a decrease in the amount of climbing and the stages are shorter.

The official unveiling of the 2024 Giro d’Italia route in Trento has revealed a 3,321km journey starting in Turin on May 4 and concluding in Rome on May 26, encompassing 21 stages and two rest days. This course was aimed to attract Team UAE’s Tadej Pogacar to the start line and the Giro have achieved that, with the Slovenian sensation recently announcing his attendance at the race.

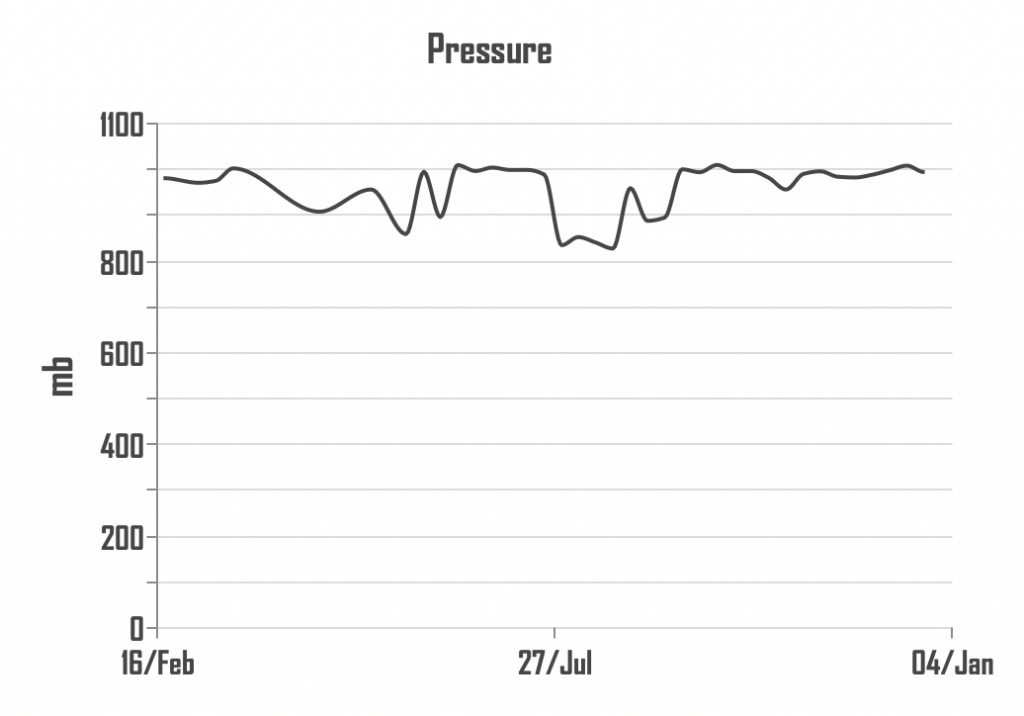

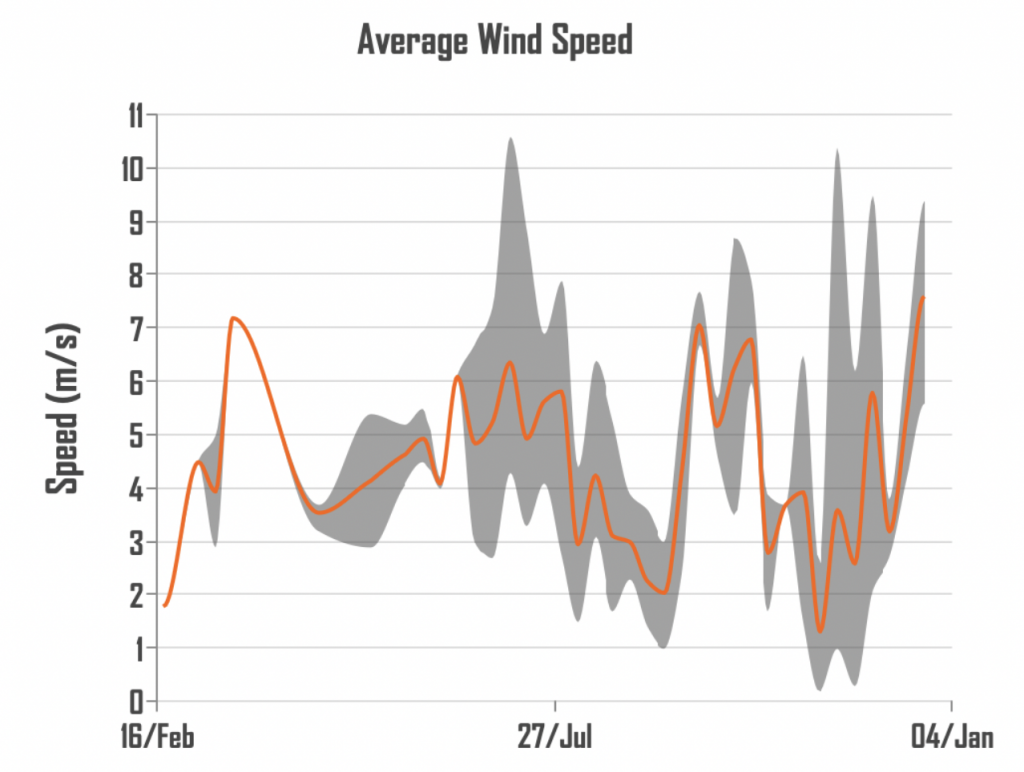

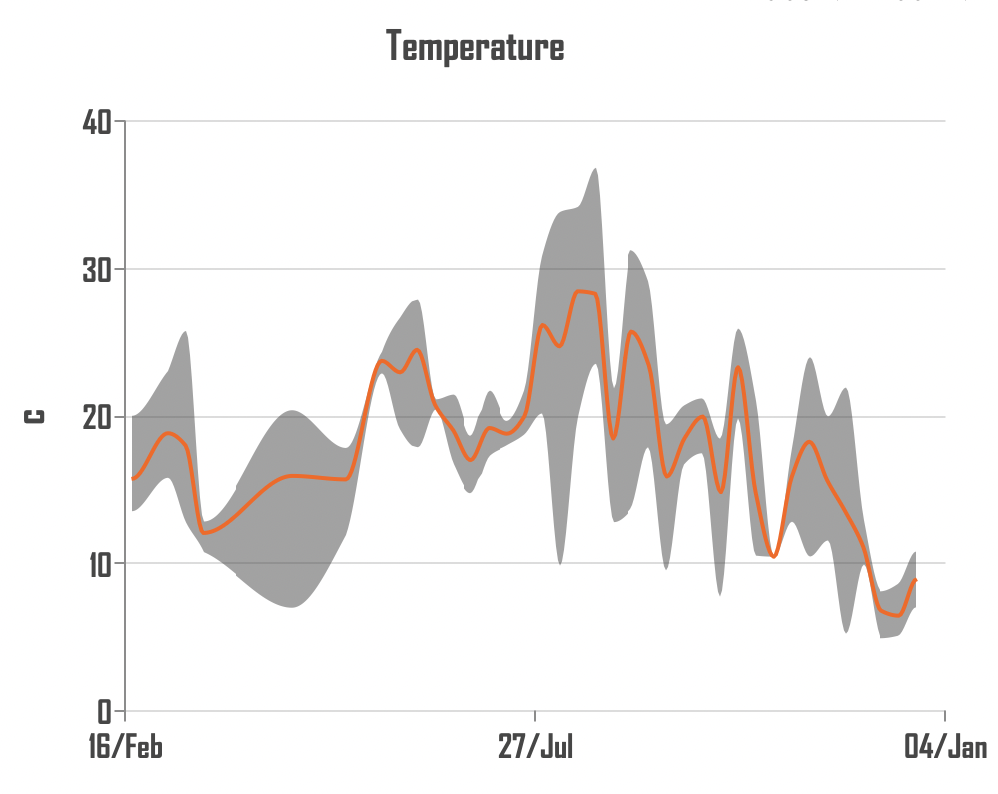

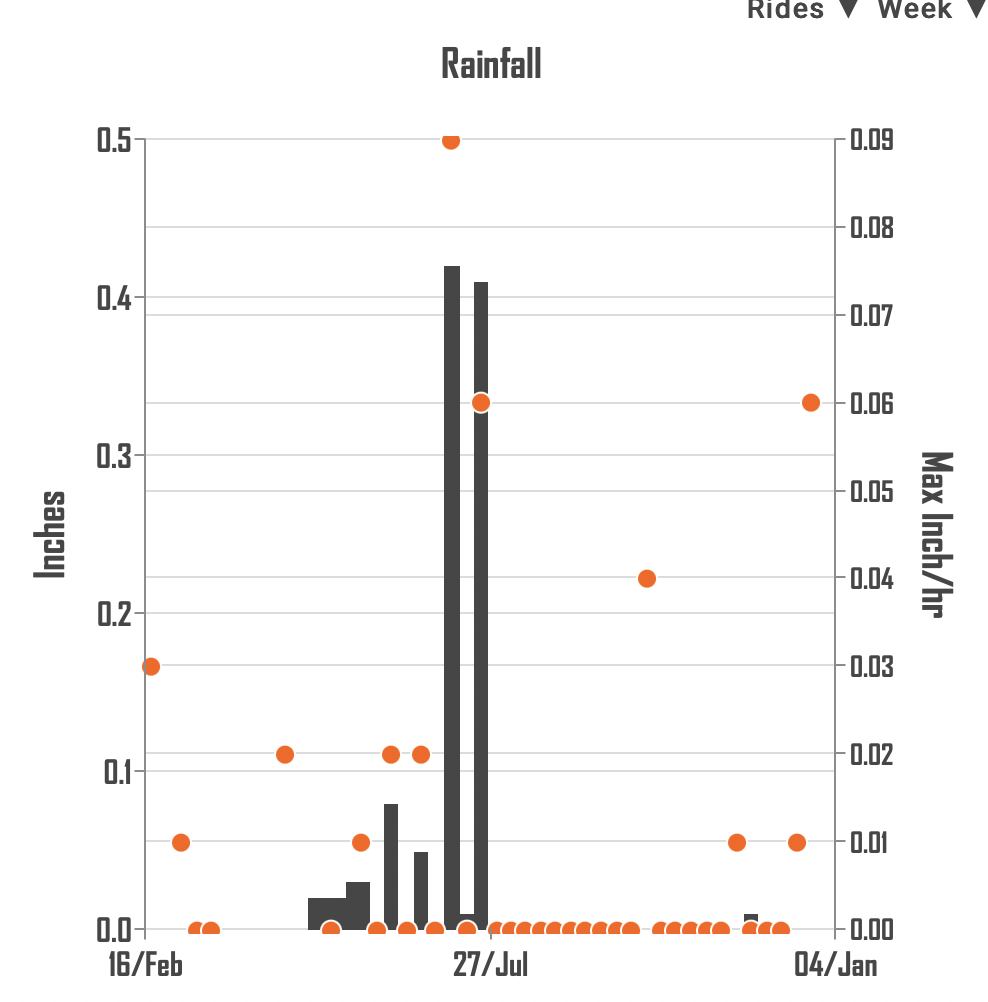

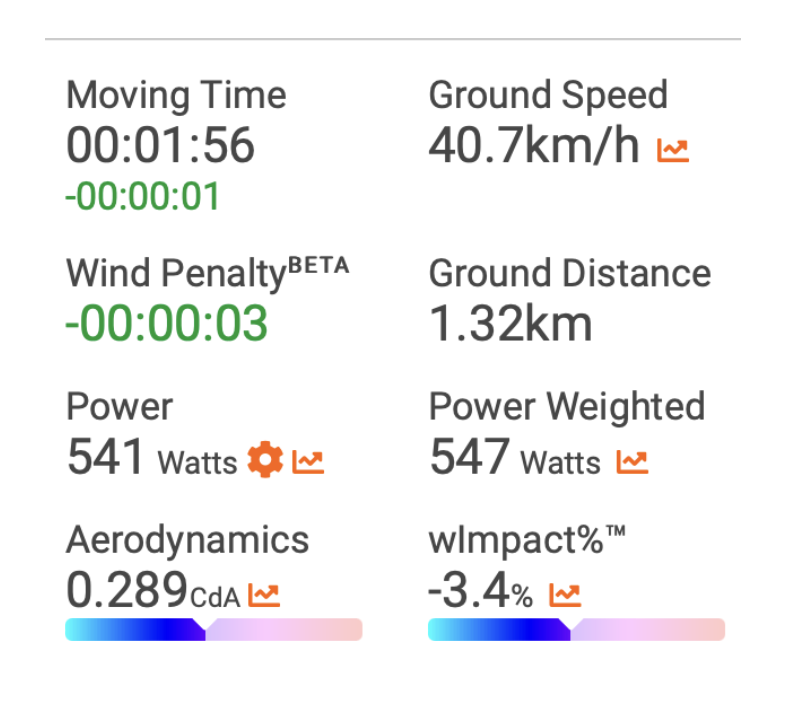

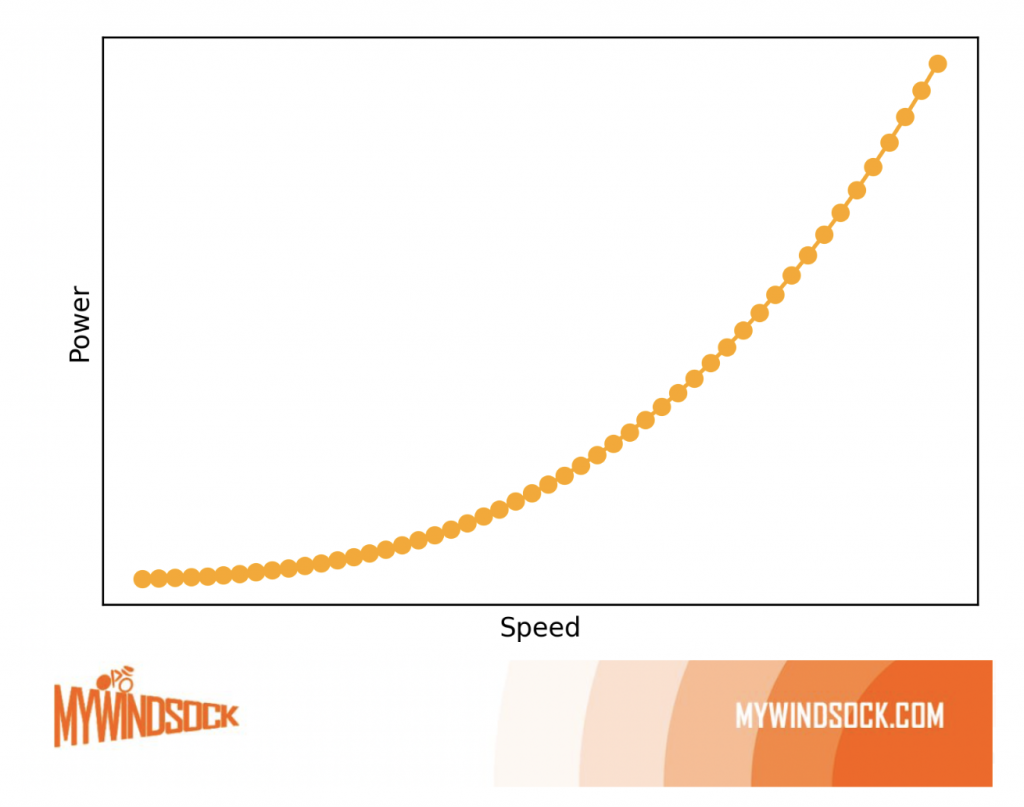

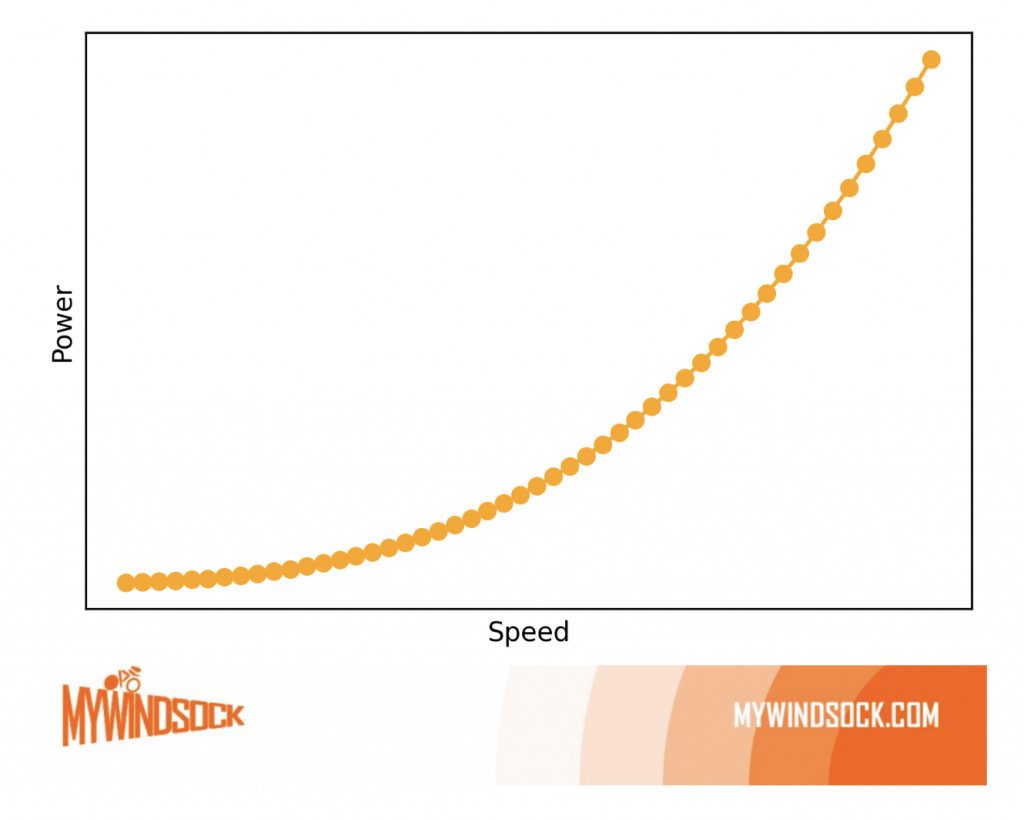

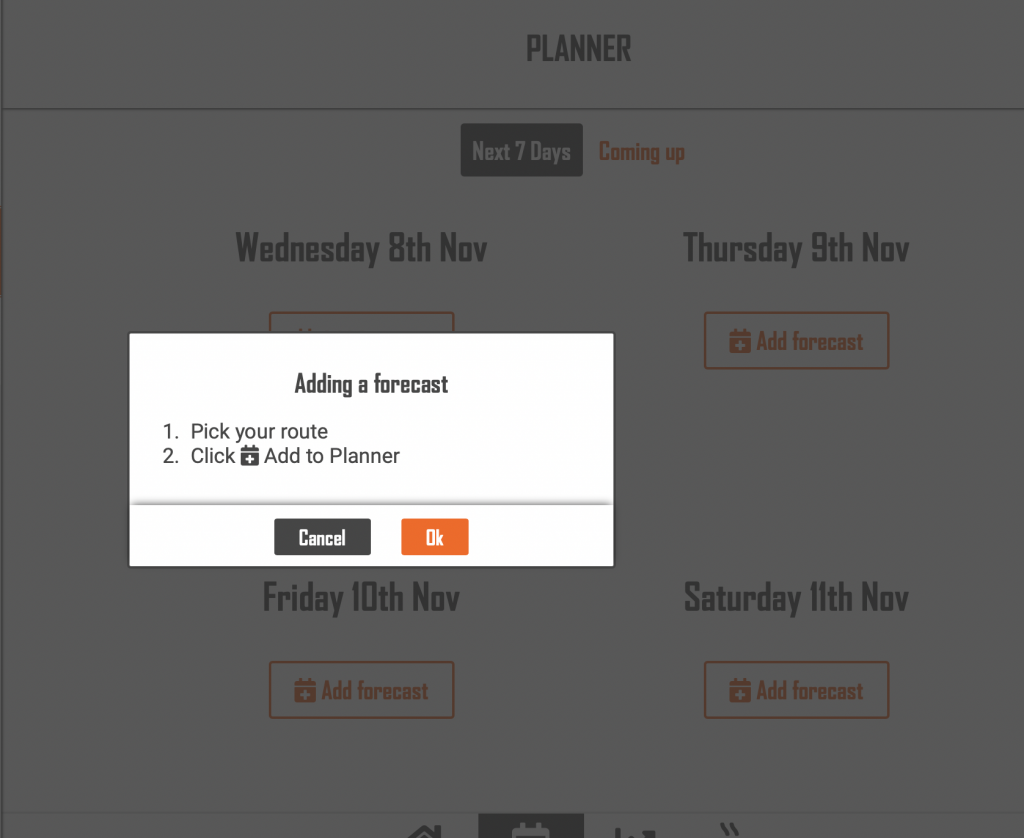

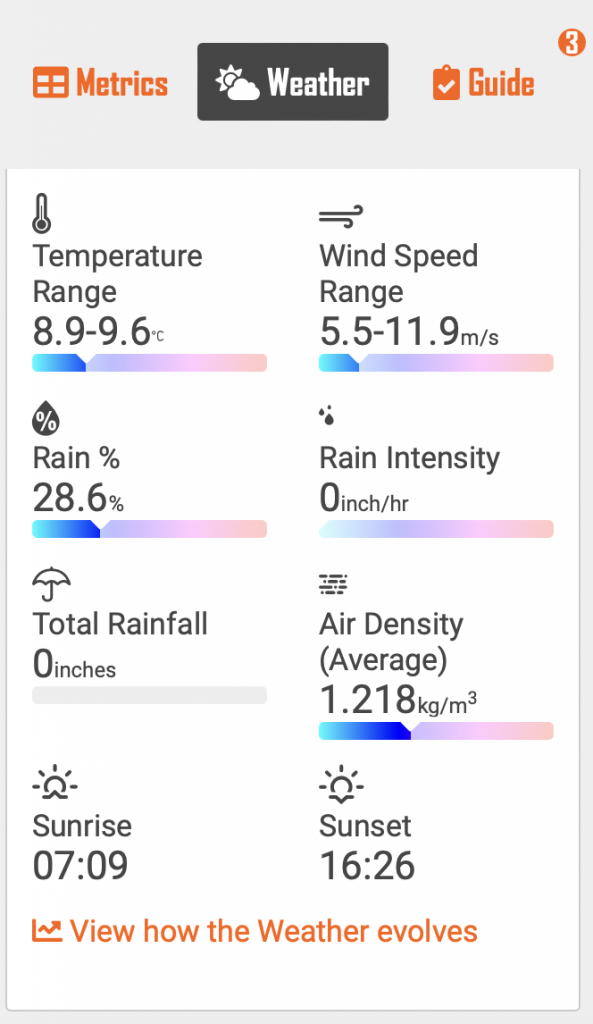

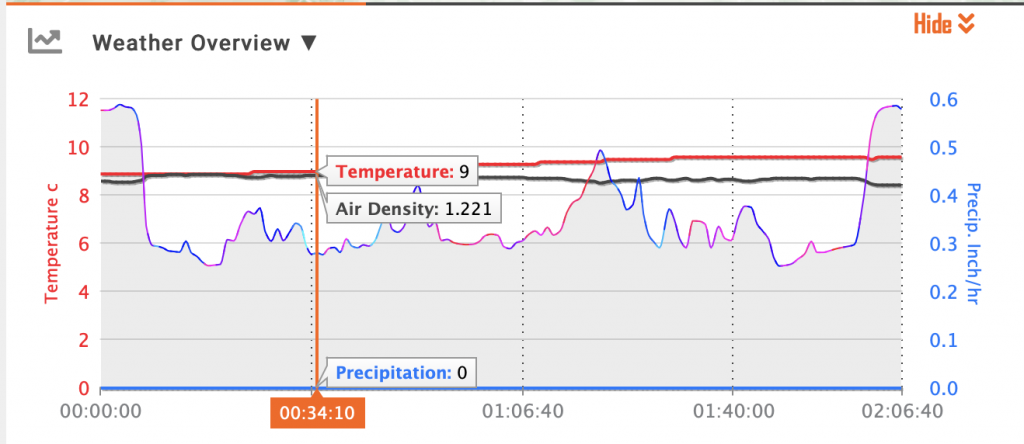

A distinctive feature of this edition is the emphasis on time trials, with a total of 68.2km spread across two tests in the first two weeks. Although slightly shorter than the 2023 total, the absence of mountainous terrain in the final time trial favours the capabilities of versatile riders. Slightly less mountains and more TT kilometres might see Wout Van Aert challenging for the GC. The final time trial will be super important, and likely conditions will play a role in the final standings. Something we will be covering here in depth.

While maintaining its reputation as the most time trial-friendly Grand Tour, the 2024 Giro sees a reduction in mountainous challenges, featuring six summit finishes. The overall elevation gain is 42,900 meters, compared to 51,000 meters in the previous two years, indicating a move towards a more balanced course. While almost 43,000m of elevation over three weeks is still an insane amount of climbing, it’s a course that will suit GC contention from a wider range of riders than previous editions.

Further building on this theme, with a total distance of 3,321km, this Giro is the shortest since 1979, contributing to a perceived lighter touch compared to the extreme dimensions of the 2023 edition. However, challenges are still prevalent, particularly in the demanding opening week, which includes tough climbs around Turin and a summit finish on stage 2. Pogacar will look to build a time buffer from the start and will likely be aggressive in the first week making for a tantalising race to watch.

Although the climbing may be less intense, the route boasts spectacular mountain stages, with three summit finishes in the first half and a challenging 220km stage with 5,200m of elevation on the Swiss border in the second week. The mighty Stelvio serves as the Cima Coppi, marking the highest point of the Giro, and the final week presents challenging double ascents of Passo Brocon on stage 17 and the formidable Monte Grappa on stage 20.

Sprinters have five clear-cut opportunities, including the final stage in Rome, while puncheurs have chances to shine with scattered small hills in the initial two weeks, adding an extra layer of excitement to the race.

The time trials – let’s take a closer look

If you want detailed coverage of the Giro stages that will be crucial then be sure to keep your eye on our blog. If you want to prepare like World Tour riders, Olympic champions and professional triathletes for your next TT or bike split, sign up to myWindsock here.

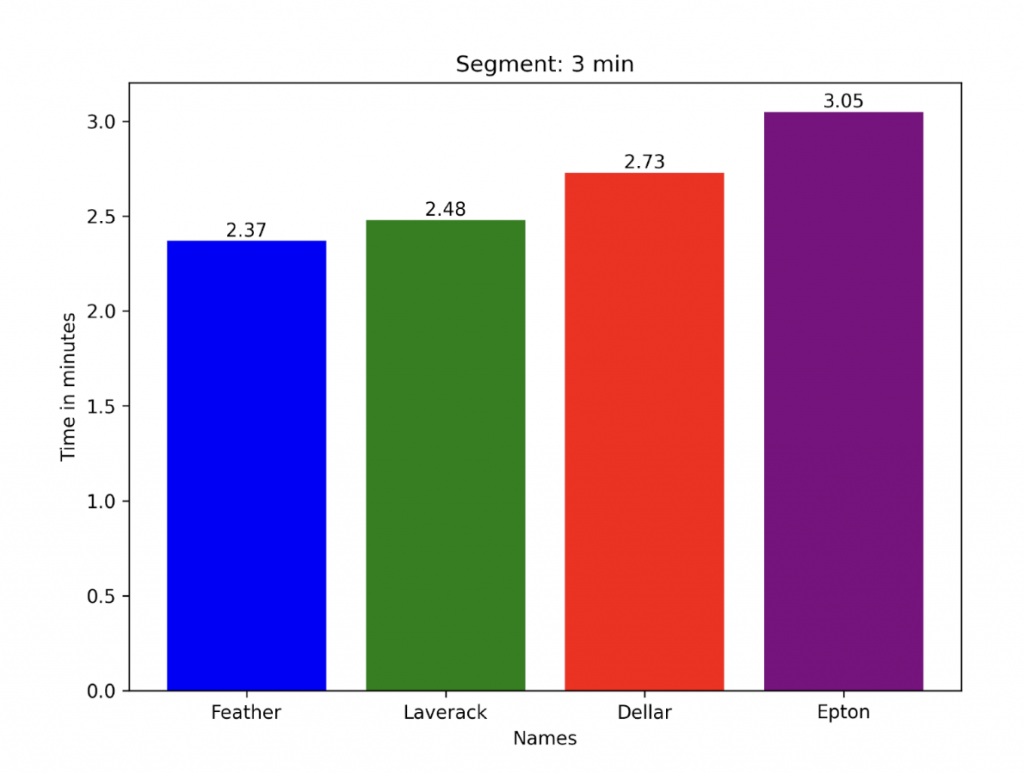

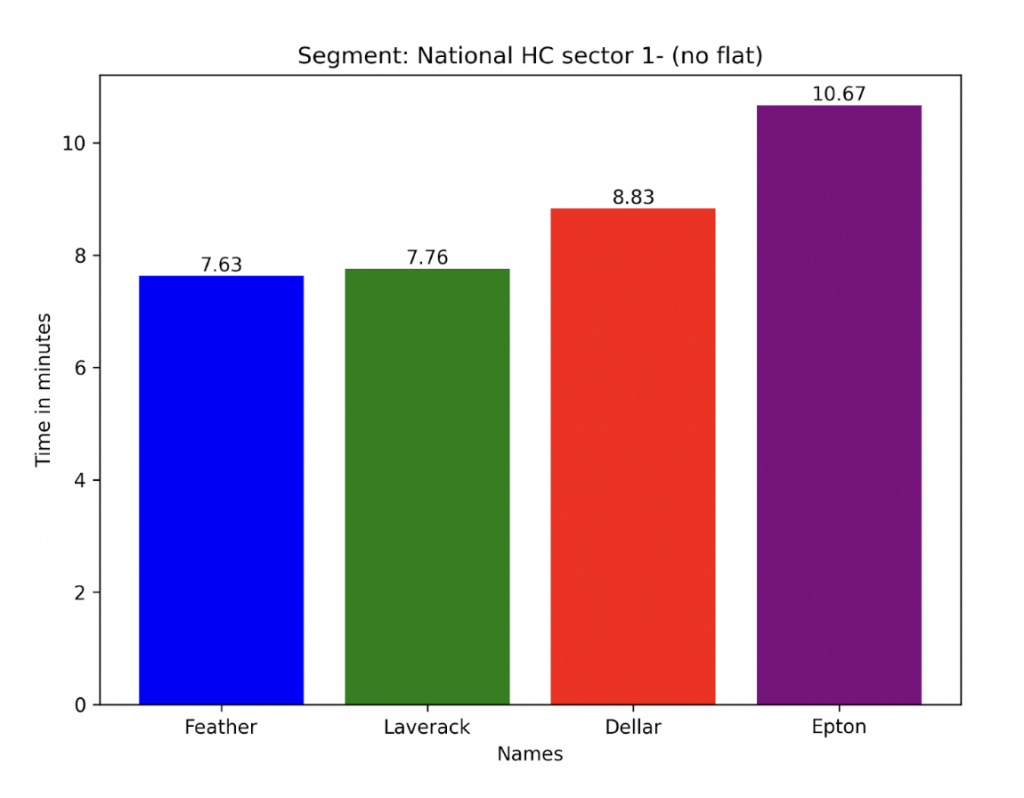

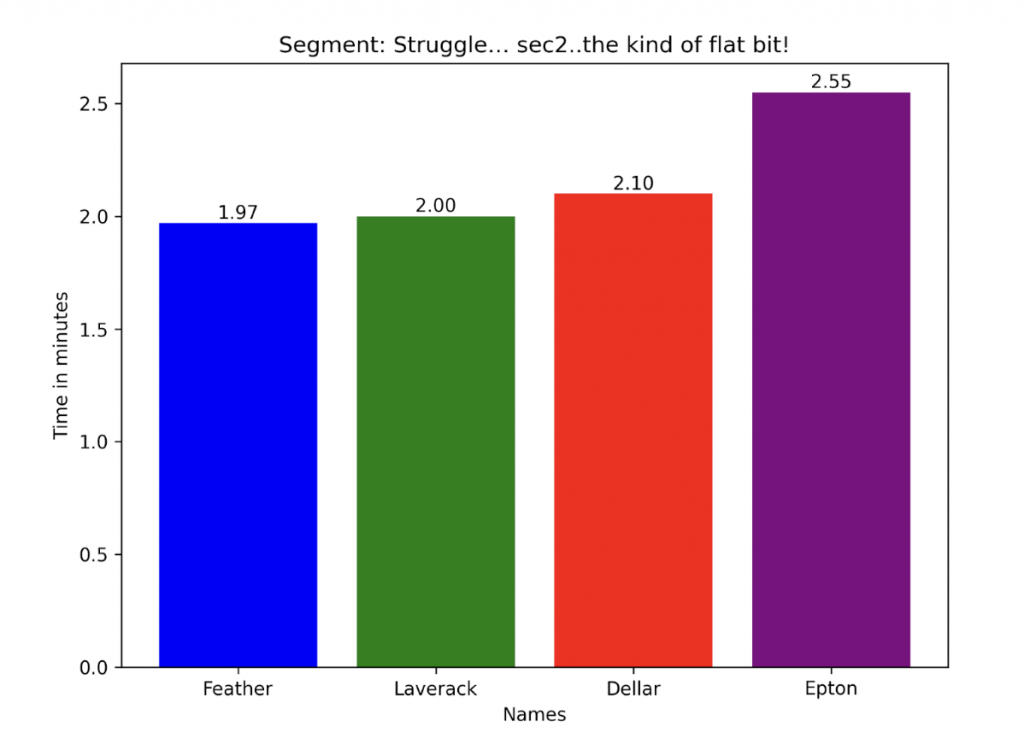

UK Time Trial Events

UK Time Trial Events