Probably not, but we thought people might google this. That said, we decided to have a proper look into it…

Echelons are exciting in professional cycling. Generally speaking, riders either love them or hate them. Crosswinds are a weird phenomenon as they can turn an innocuous piece of road into a very tricky section as riders in the wheel get no shelter if they’re in the wrong place. I find it can be a tricky concept to visualise but with a diagram (and the help of myWindsock) we can see when crosswinds might develop. Every year we see crosswinds in the classics season and the echelons occasionally pop up during grand tours. They’re exciting in grand tours particularly as GC time gaps can occur when they’re not expected.

Predicting these crosswinds can be tricky. For example, crosswinds can happen but echelons do not form due to lack of motivation. Sometimes, a team tries to create echelons but the wind doesn’t blow hard enough or for long enough. Anything that relies on the behaviour of humans and the weather can be tough to predict – myWindsock is the perfect place to check whether the conditions are right but we can’t help what people do…

What should a rider do in crosswinds?

In crosswind conditions, road cyclists encounter additional drag and destabilising lateral forces. However, cyclists have found a way to minimise these forces by adjusting their spatial formation, forming an echelon. An echelon refers to a diagonal single pace line of riders positioned in a staggered manner across the road. This configuration is distinctly different from the formations used in wind-free conditions.

In a basic configuration with four riders at a yaw angle of 50 degrees, a rider positioned within the echelon experiences less than 30% of the drag faced by the rider at the rear, who is exposed to the crosswind. Adopting an echelon becomes advantageous only when the yaw angle exceeds 30 degrees. At this critical yaw angle, the drag on the rider at the rear doubles when the distance between the two groups increases from 10 cm to 1 m in real scale. Yaw angle is essentially the effective wind angle, so if you’re riding into a headwind the yaw angle is zero degrees and it increases as we move the wind direction around the rider.

When will crosswinds cause echelons?

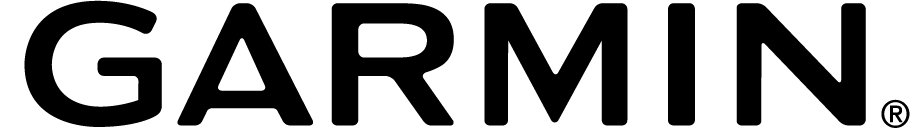

An echelon is only worth being adopted when the yaw angle is above 30 degrees. Cross tail winds are also more effective for splitting the peloton as the effective draft in the wheels is lower and the speeds are higher (so gaps in distance open up faster). If the wind is blowing hard from an angle large enough, crosswinds have the potential for forming echelons.

Using myWindsock to predict crosswinds

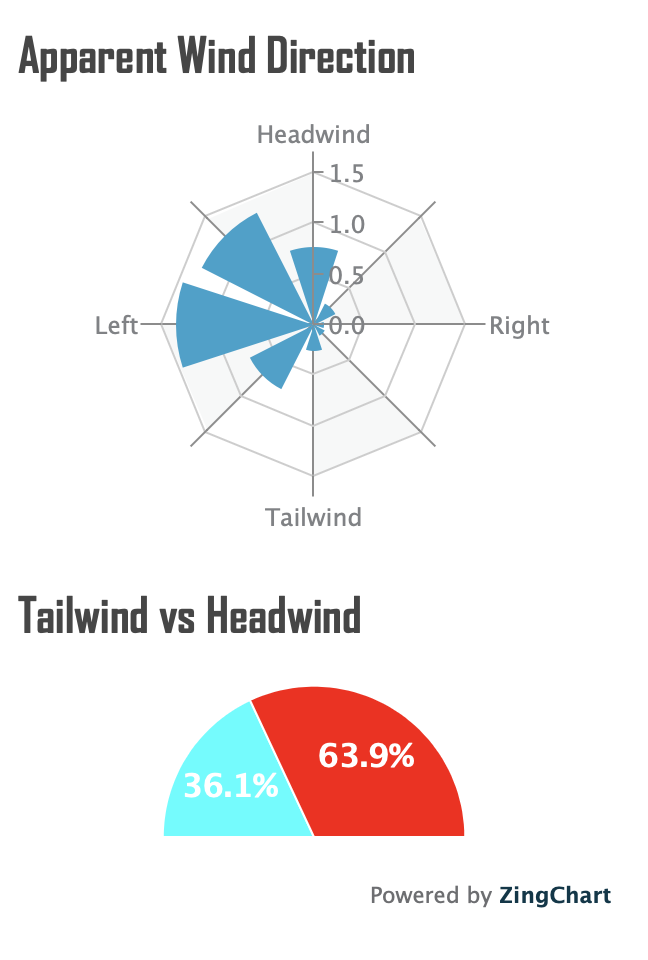

At a shallow wind angle (in the direction of a headwind) the faster the bunch rides, the closer to zero the yaw angle gets. This means that any wind blowing in the direction of a rider’s hip round to their backside is what’s most likely to cause crosswinds. As, at the time of writing, the Tour de France is on, we will take stage 3 as a ‘crosswind potential stage’. To decide whether or not a crosswind will form echelons, we need to ask a couple of questions – what direction is the wind blowing? How long is the wind blowing for? How hard is it blowing? Who is motivated to make it happen?

To us, crosswinds will blow in this stage but it’s unlikely to cause too much grief. GC teams will want to pay close attention as the race turns in land toward the finish where conditions are optimal for someone to try something as the wind is in the right direction and the distance to the finish is small enough that it’s not obscene to pace all the way to the line from there.

We know that myWindsock is used in many a team bus in the World Tour – so if you’ve got a bunch race coming up in a windy place (or just want to stick it to your clubmates when they don’t expect it) check out myWindsock and sign up here.

UK Time Trial Events

UK Time Trial Events