Physics was not everyone’s cup of tea from their school days, however we thought the myWindsock website needed a place which did explain some of the basics of cycling aerodynamics to give our curious users a place to begin to look under the hood. This blog will give you enough of an idea to understand how myWindsock makes predictions but without overwhelming detail (or giving away too much of the magic).

As such, we need to skip some steps to communicate the basic point without losing people with unnecessary formalities. This will possibly irritate readers with advanced degrees in Aero Engineering and I suggest they stop reading immediately.

Imagine you’re riding a bike at constant speed through the air.

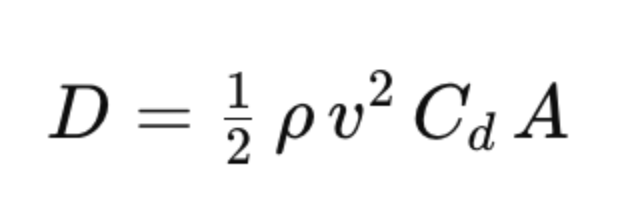

We’ll start with the drag equation, skipping on the details of how we get from physics first principles to it. We can calculate the drag force (the number of Newtons a cyclist is pulled back by) with this formula, which will look very simple or very confusing, depending on when you last did maths and how much you enjoyed it at the time.

In English, this says that Drag (D) is equal to air density (the Greek letter rho) multiplied by velocity squared (v, multiplied by itself) multiplied by the product of drag coefficient (Cd) and frontal area (A). In even simpler terms, you calculate the drag on a cyclist by multiplying a bunch of numbers together – some of which are to do with the cyclist and others to do with the environment.

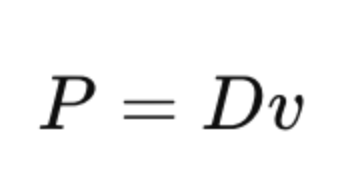

We can also calculate the power needed to ride at this constant speed using the following equation. This is useful to us because we are able to measure power much more easily than we are able to measure drag while we’re out on the road.

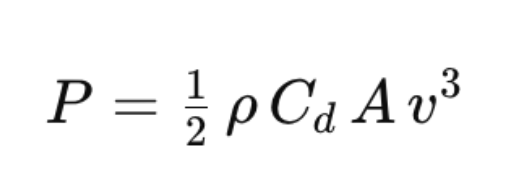

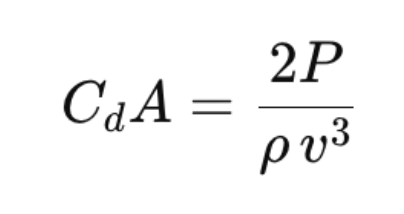

Using some algebra (sorry) which you’re welcome to try at home, we can combine these two equations and obtain the following result…

This tells us how we can calculate the aerodynamic drag required to ride at the constant speed we mentioned earlier. As a cyclist, you may know what power you’re riding at because you’ve got a powermeter on your bike. You are unlikely to know your CdA. As such, we can re-write the equation with stuff we “know” (reasonably estimate or measure to sufficient accuracy) on one side of the equals and the stuff we don’t know (or that’s much harder to estimate) on the other side of it.

Time for a quick disclaimer, the power on our powermeter here displays all the power we are using to overcome all resistive forces, but we’re only talking about aero power here so we are going to have to make some slightly wild, but fine for illustrative purposes, assumptions. Let’s try and plug in some numbers.

Right now, where I am, the air density is 1.19 kilograms per metre cubed (which means, if you were to somehow weigh a cube of air that’s one metre by one metre by one metre it would weigh 1.19kg) and we’ll imagine I’m doing 30kph on my bike with my power meter reading 220W on a road and we’ll assume forces that aren’t related to air resistance make up 20% of our power output. As such, the amount of power we are using against the air is 176W. If we plug all of those numbers into the expression above it gives us an estimate for our CdA of 0.517.

This isn’t a complete description of how myWindsock calculates CdA, nor is it a rigorous explanation of the equation of motion of a cyclist but it gives you a fairly solid introduction into the mathematics of cycling…at least at a constant speed on a flat road.

UK Time Trial Events

UK Time Trial Events